Posted May 20, 2020 from The Ringer —

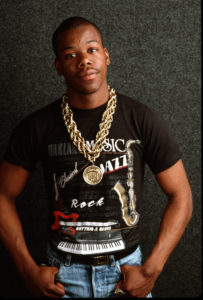

On February 12, 1990, rapper MC Hammer released his third album, Please Hammer, Don’t Hurt Em. Thanks to the mega-hit “U Can’t Touch This,” it would go on to spend 21 nonconsecutive weeks at the top of the Billboard charts—still the only rap album to achieve this feat—and remains one of the top five best-selling rap albums in history. It was also the first time a rap album was nominated for Album of the Year at the Grammys.

The following month, on March 20, rap group Digital Underground released its debut album, Sex Packets, propelled by the hilarious, raunchy “The Humpty Dance,” which went platinum.

Just a few weeks later, on April 3, another spectacular debut album was released, En Vogue’s Born to Sing, which featured the hit song “Hold On” and introduced the world to still-unmatched vocal-harmony pyrotechnics.

On May 8, R&B phenoms Tony! Toni! Toné! released their second album, The Revival, scoring major hits with “Feels Good,” “It Never Rains (in Southern California),” and “Whatever You Want.” Finally, on September 11, Too Short, the “godfather of Bay Area hip-hop,” released his fifth studio album, Short Dog’s in the House, which went platinum and featured the hits “Short but Funky” and the Donny Hathaway–inspired “The Ghetto.”

The common thread among these five 1990 releases? All the artists trace their musical roots to Oakland, California. The Tonies, MC Hammer, and Money B of Digital Underground are all Oakland natives, as are Denzil Foster and Thomas McElroy, the production team behind the Tonies’ first two albums and the creation of En Vogue. While not Oakland-born, Too Short moved to “the Town” from L.A. with his family when he was a teen.

How did all these cultural touchstones emerge to make Oakland the center of black popular music 30 years ago? There’s not one all-encompassing answer. For one, as Digital Underground founding member Money B points out in an interview, this was a pivotal period in hip-hop more broadly: “Go from ’88, ’89, ’90, ’91, and ’92 and just look at all the hip-hop albums that are classics.” Comparing this period to 2019, he says, “Last year, maybe 100 times more albums came out, but how many classics came out?” Nonetheless, several forces—not only musical, but also political, geographic, and ideological—converged to thrust Oakland into the national cultural zeitgeist in 1990.

The Bay Area has long been recognized as having an independent spirit, of doing things a bit differently than the rest of the country. Whether it’s the free-loving hippies of San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury district and Berkeley’s Telegraph Avenue who popularized the public consumption of illicit drugs, or the rise of the militant Black Panther Party in Oakland, the Bay Area is where many people have come in the past half-century to buck the status quo.

These political and social movements affected Oakland’s music scene: Many local musicians coming up in the 1980s had personal ties to the Black Panther Party, such as having a parent who was a member (like Money B and Tupac, who bonded over this when Tupac joined Digital Underground) or being a recipient of the Panthers’ famed free breakfast program (like the Tonies’ D’wayne Wiggins). As cultural historian Rickey Vincent, author of two renowned books on funk and soul music, says, “Oakland’s ties to pop culture are interwoven with the militant Black Power self-determination milieu.”

These political and social movements affected Oakland’s music scene: Many local musicians coming up in the 1980s had personal ties to the Black Panther Party, such as having a parent who was a member (like Money B and Tupac, who bonded over this when Tupac joined Digital Underground) or being a recipient of the Panthers’ famed free breakfast program (like the Tonies’ D’wayne Wiggins). As cultural historian Rickey Vincent, author of two renowned books on funk and soul music, says, “Oakland’s ties to pop culture are interwoven with the militant Black Power self-determination milieu.”

The Bay Area’s legacy of political activism—the Panthers as well as the Women’s Liberation movement and the Free Speech Movement that originated at UC Berkeley—was influential for the region’s music, said Digital Underground founding member and Berkeley native Jimi “Chopmaster J” Dright in a 2015 interview. The Bay Area also boasted an eclectic array of artists in the 1970s, including Santana, the Grateful Dead, and Sly and the Family Stone.

“We’re not trying to be like the East Coast. We’re not trying to be like anybody. We’re on the edge of the world,” Vincent says. “Oakland was accepting of people that did things in an original way.”

The Bay Area’s cultural diversity and eclecticism also have a downside, says Denzil Foster. It’s never a good thing commercially for a place not to have a distinctive sound associated with it. “I think [cultural eclecticism is] what made the Bay Area special but made it harder [for] people to grasp on, like the industry,” Foster says. Unlike Seattle with its grunge sound, the Bay has never had that one defining style.

However, there was a sense back in the late 1980s that musicians from the region had to come with a fresh sound. Bay Area artists were never keen on emulating the “originators,” particularly in hip-hop, says local hip-hop DJ and journalist Davey D. Being so physically distant from New York, Bay Area rappers didn’t feel pressure to conform to the sound that was the sonic blueprint for hip-hop. “If you said New York was a lion, L.A. was a lion, the Bay would be a tiger. … It’s not gonna be the king, but you’re not really gonna mess with it too much,” he says.

However, there was a sense back in the late 1980s that musicians from the region had to come with a fresh sound. Bay Area artists were never keen on emulating the “originators,” particularly in hip-hop, says local hip-hop DJ and journalist Davey D. Being so physically distant from New York, Bay Area rappers didn’t feel pressure to conform to the sound that was the sonic blueprint for hip-hop. “If you said New York was a lion, L.A. was a lion, the Bay would be a tiger. … It’s not gonna be the king, but you’re not really gonna mess with it too much,” he says.

Oakland’s hip-hop scene was never going to rival that of New York or L.A., but at least, as Davey D puts it, the Bay didn’t have “a second-city complex”—the fear of not measuring up to New York, like Chicago or Philly did. Oakland rappers didn’t feel beholden to New York to bestow validation upon them. Take Too Short, for example: “He’s not trying to ingratiate himself with New Yorkers,” Davey D says. “They booed him at his album party in New York. But what Short knows, what people later found out, is that everywhere else around the country, they loved it,” particularly in the South. “So the Bay artists very quickly were able to understand that there’s more to life than just New York, because they’ve already existed that way.”

Too Short also created a template for rappers from the South and other regions, Davey D says. Not only did artists elsewhere like his relaxed, “folksy” rapping style, but “he let people know that they can be themselves.” Even among Oakland-based rap artists, one would be hard-pressed to imagine three styles more distinct than those of Too Short, MC Hammer, and Digital Underground. As Vincent says, “Too Short’s core constituency is the East Oakland street scene where the mack is the hero,” while Hammer was more “wholesome” and palatable for white audiences. Davey D adds, “People were allowed to have their lanes.”

And Digital Underground definitely had its own, third lane. Chopmaster J recalled that the group originally aspired to be “the Black Panthers of hip-hop,” but Public Enemy had already taken that slot. They also liked the hippie vibe, but saw that De La Soul had the daisy emblem on their debut album cover. “So we just decided to be ourselves, which was an eclectic blend.”

Still, as Money B says, stylistic diversity wasn’t a uniquely Bay Area thing, but rather an unwritten rule of hip-hop at the time: “Back then it was not OK to be a biter or copy. If somebody was doing a style, you couldn’t do it,” or you’d get no respect. What was unique to the Bay, especially Oakland, however, was a culture of hustling, he says. Given that there were no nationally known Bay Area rappers until the late 1980s, there was a sense that up-and-coming artists had to find a way to put out records themselves. This is why the Bay Area has been so strongly associated with the independent hip-hop scene.

Money B remembers witnessing Too Short’s progression, “from selling tapes in the neighborhood to actually distributing tapes through record stores independently, to actually pressing an independent record.” For him, Too Short was the blueprint for independent rappers. And when he finally got a deal with Jive Records and recorded his most successful album, 1989’s Life Is … Too Short—and Money B saw the Tonies and MC Hammer making moves with their first albums—he finally started to believe a rapper didn’t have to be from New York or L.A. to make it big.

Money B remembers witnessing Too Short’s progression, “from selling tapes in the neighborhood to actually distributing tapes through record stores independently, to actually pressing an independent record.” For him, Too Short was the blueprint for independent rappers. And when he finally got a deal with Jive Records and recorded his most successful album, 1989’s Life Is … Too Short—and Money B saw the Tonies and MC Hammer making moves with their first albums—he finally started to believe a rapper didn’t have to be from New York or L.A. to make it big.

Too Short wasn’t the only self-made Oakland artist. Davey D notes MC Hammer’s “hustling aesthetic,” suggesting he was a hip-hop entrepreneur years before Diddy or Jay-Z were household names—he and his brother bought stakes in the clothing company Troop and began opening franchise stores in local malls. Similarly, hip-hop historian Jeff Chang remembers Hammer, just like Too Short, selling his tapes on consignment in local record stores. Hammer may not have had the musicianship or raw talent of the Tonies, En Vogue, or Shock G, but he had, as Chang put it, “universes more show sense [as an entertainer] than all of them put together.”

If there’s a common denominator among the styles of these five albums from 1990, it’s funk and soul. “Too Short, Hammer, Digital Underground, [the San Francisco–born rapper] Paris—they’re all based on the funk,” Vincent says. And this didn’t apply only to Oakland’s rap scene: “We were all babies from the funk era,” says ex-Tonies frontman Raphael Saadiq. Both Saadiq and Vincent recall that Marvin Gaye’s famous live version of “Distant Lover” was recorded at the Oakland Coliseum in 1974, where, as Vincent says, the crowd screamed so loud that the speakers blew out.

Saadiq draws a direct line from funk and soul artists to the music of each of the Oakland artists: For Too Short and Digital Underground, it was Bootsy Collins and Parliament-Funkadelic; for MC Hammer it was Rick James (“U Can’t Touch This” sampled James’s “Super Freak”); for the Tonies, it was Earth Wind & Fire, the Commodores, and Delfonics; and for En Vogue it was the Supremes. All of his peers, Saadiq concludes, were “trying to mimic our funk heroes.”

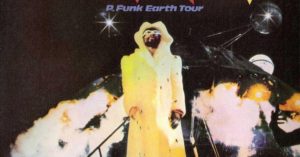

Three years after the live performance of “Distant Lover,” George Clinton and P-Funk landed the mothership in Oakland. By this time, the group had already scored a major hit with “Give Up the Funk (Tear the Roof Off the Sucker),” and had begun the massive undertaking that was the P-Funk Earth Tour in 1976 and ’77. In May 1977, a live double album of the tour made up of performances from the Oakland Coliseum and Los Angeles Forum was released.

Three years after the live performance of “Distant Lover,” George Clinton and P-Funk landed the mothership in Oakland. By this time, the group had already scored a major hit with “Give Up the Funk (Tear the Roof Off the Sucker),” and had begun the massive undertaking that was the P-Funk Earth Tour in 1976 and ’77. In May 1977, a live double album of the tour made up of performances from the Oakland Coliseum and Los Angeles Forum was released.

Vincent, who attended the Oakland show, remembers the huge spaceship prop landing. And then, “they did a whole gospel church invocation in the middle of the heavy metal funk they were doing,” he recalls. “They got four horn players on one side and four guitars on the other side. … And all this concept was like—wait, they are sort of claiming domination of the tradition right here.” The next year, P-Funk released “Flash Light” and “One Nation Under a Groove,” cementing the group’s iconic status in black popular music.

The live album had added significance for local musicians, Vincent says. On the album, when the spaceship landed, the vocalist asked the audience, “Oakland, do you wanna ride? I can’t hear you. Oakland do you wanna ride tonight?” Several rap artists from the Bay—such as The Coup and Del the Funky Homosapien—later sampled that moment, Vincent adds, essentially claiming P-Funk as an Oakland thing.

“P-Funk really defined black liberation,” says Vincent, which he thinks is one reason why the group appealed so much to black folks on the West Coast. “We weren’t bound by these Jim Crow notions of what black advancement is. People came out west to be free … from all the constrictions and prescriptions of what success is, of what liberation is.”

Black migrants who came west after World War II also brought important Southern traditions, like gospel. Saadiq emphasizes the influence of Bay Area gospel groups for him, like the Gospel Hummingbirds and the Edwin Hawkins Singers. “The gospel was strong, you know, because most of our families migrated from the South, from Louisiana, Mississippi.” As for the links between the South and the Bay Area, “we really [were] like a lot of Southern kids who had … those Southern twangs.”

While all five of the significant Oakland albums celebrating their 30th anniversary are indebted to funk in some way, no one paid more tribute to P-Funk’s legacy than Digital Underground. In the episode of the Netflix documentary series Hip-Hop Evolution dedicated to the Bay Area, frontman Shock G said his goal was to incorporate elements of P-Funk into their music. He said, “I don’t know if Digital Underground coulda happened anywhere else. It happened in the Bay cuz I’m totin’ that P-Funk flag, and the Bay Area was the most, of a collection of people, into funk,” he said.

While all five of the significant Oakland albums celebrating their 30th anniversary are indebted to funk in some way, no one paid more tribute to P-Funk’s legacy than Digital Underground. In the episode of the Netflix documentary series Hip-Hop Evolution dedicated to the Bay Area, frontman Shock G said his goal was to incorporate elements of P-Funk into their music. He said, “I don’t know if Digital Underground coulda happened anywhere else. It happened in the Bay cuz I’m totin’ that P-Funk flag, and the Bay Area was the most, of a collection of people, into funk,” he said.

The whole concept of having different iterations of the group—and of Shock G having alter egos like Humpty Hump and Piano Man (all three of whom appear on their song “Doowutchyalike”)—came directly from P-Funk’s different configurations.

The influence even worked its way into the production on Digital Underground’s biggest hit: “We sampled ‘Let’s Play House’ by George Clinton for ‘Humpty Dance,’” Chopmaster J recalled. “Then … a loop of the bass ended up getting stuck in a sequencer, and it was a wonderful, beautiful mistake. It kind of locked in there when we had too much MIDI gear hooked up and too many things going at once where that bass was being played … that ended up looping in a way that was something we hadn’t heard before and quite honestly no one’s ever been able to duplicate since.”

If Digital Underground looked back to the late 1970s for inspiration, the production and songwriting team of Denzil Foster and Thomas McElroy tried to take R&B into the future via new jack swing. In the mid-1980s, Foster and McElroy had formed part of the Timex Social Club (“Rumors”) and then Club Nouveau (“Lean on Me”), groups that are largely unsung pioneers of new jack swing. “Rumors” was released in 1986 and contained the hallmarks of the style, namely the merging of hip-hop beats and production techniques with R&B-style vocals. This was a year before the credited creator of new jack swing, Teddy Riley, formed his first group, Guy.

“All the good songs were R&B songs and all the good grooves were rap grooves,” Foster recalls. “And so it was like, ‘Why can’t we just sing a good song over a good beat, you know? Why does it have to be a ballad?’” Foster says this was the template for Club Nouveau, adding “I won’t say it was like a Bay Area sound, but it became a formula that kind of worked for everybody.”

Foster and McElroy left Club Nouveau and struck out on their own as a production team, signing a deal with Wing Records in 1988. The first group they wanted to produce was the Tonies, whom they already knew about from the Oakland scene. Ironically, Wing Records had already passed on the Tonies, telling Foster and McElroy that bands were “played out.” The label saw everyone starting to jump on the hip-hop bandwagon, i.e., using DJs, synthesizers, and drum machines instead of live backup musicians.

The problem was that the Tonies had incredible musicianship, but weren’t commercially minded. Saadiq recalls, “We were way too musical. That was the problem.” Their training at Oakland’s Castlemont High School, which was essentially a school of the arts in the 1970s and ’80s, had provided them with professional-level chops. But, Saadiq says, all they had was their musicianship: “We didn’t have strong song structure. We didn’t have great beats.”

The problem was that the Tonies had incredible musicianship, but weren’t commercially minded. Saadiq recalls, “We were way too musical. That was the problem.” Their training at Oakland’s Castlemont High School, which was essentially a school of the arts in the 1970s and ’80s, had provided them with professional-level chops. But, Saadiq says, all they had was their musicianship: “We didn’t have strong song structure. We didn’t have great beats.”

Although Wing was hesitant to give the Tonies another chance, Foster and McElroy convinced the label that they could make the appropriate adjustments to make the band more appealing to Top 40 audiences. Foster says the goal was to make the Tonies’ music “not so bandy, but still leave the band elements there, so people [would] recognize that it wasn’t just a singing group. ’Cause they didn’t want to be confused for that either.”

Saadiq was thrust into the lead singer role, which had been formerly occupied by his brother, D’Wayne Wiggins. “Raphael had a unique sound,” Foster says, “like a youthful kid singing. I know that works well on radio, it’s identifiable and people could go, ‘Oh, I know who that is immediately.’” Though it’s hard to imagine now because of how successful he has been as a vocalist, Saadiq was very resistant to put his bass down and be the frontman, saying the idea scared him: “I was a little guy and, you know, little guys get looked at like, they might be sissies ’cause they sing, and I didn’t really want to sing. I just wanted to play because the bass made me feel like the big man, you know? It was like the anchor of all the music.” When he began singing, he says, “I felt like Linus without my blanket.”

At the end of the day, Saadiq says, Foster and McElroy “brought a sound to us” and jump-started his career by helping the Tonies get the shot they needed.

The template that began with the Tonies was carried over into Foster and McElroy’s creation of En Vogue. As McElroy said in a 2012 interview, “The approach for their first album was much more of a raw, street approach. … When we first did ‘Lies’ and ‘Hold On,’ I was thinking about making those tracks more hip-hop sounding and a little bit grittier.” In fact, Davey D recalls speaking with Bill Stephney (who recruited Public Enemy for Def Jam back in 1986) about En Vogue, and Stephney calling Born to Sing a hip-hop record instead of an R&B record.

Foster and McElroy achieved En Vogue’s sound through an unexpected source of inspiration. It was 1989, and they knew black popular music was all about new jack swing—which, of course, they had helped bring about. But something else happened as they were in the middle of recording Born to Sing: Soul II Soul’s debut album dropped with “Back to Life” and “Keep on Movin.’” Foster says that the album changed everything for him and McElroy. “All of a sudden this beautiful, kind of subdued piano and drum and vocals came on the air and it just turned into the biggest dance record that year. And it was like, ‘Wait a minute, how did a 90 [beats per minute] song turn into the biggest dance record?’”

Foster and McElroy achieved En Vogue’s sound through an unexpected source of inspiration. It was 1989, and they knew black popular music was all about new jack swing—which, of course, they had helped bring about. But something else happened as they were in the middle of recording Born to Sing: Soul II Soul’s debut album dropped with “Back to Life” and “Keep on Movin.’” Foster says that the album changed everything for him and McElroy. “All of a sudden this beautiful, kind of subdued piano and drum and vocals came on the air and it just turned into the biggest dance record that year. And it was like, ‘Wait a minute, how did a 90 [beats per minute] song turn into the biggest dance record?’”

The vocals weren’t competing with the music, Foster says, “which just changed our whole mind-set of what to do with [En Vogue] … we can now work their vocals and basically strip everything from it and make them a true vocal group.” And, he adds, that’s how “Hold On” came about. Soul II Soul’s style inspired Foster and McElroy to substitute intricate vocal harmonies for melodic lines that would usually be played by a string instrument or flute. The idea was to “keep the funk in there” but with a slower tempo and incredible vocals.

While En Vogue and the Tonies would likely have triumphed even without a big push from local media because of their talent and great production, Bay Area radio stations and record stores played an instrumental role in helping the rap acts get noticed nationally. Before Digital Underground was signed by a major label, Chopmaster J was able to get the group played on local hip-hop shows on community radio stations like KPFA and UC Berkeley’s KALX (where, as a student, Davey D began his radio DJ career).

Shortly thereafter, the Bay Area’s sole commercial hip-hop station took notice. “In 1988, KMEL had a show called Kiss It or Diss It, and they played it on the air and people ‘kissed’ it, they liked it, and so we were put into a light rotation over at KMEL, which also led us to being the local act that got to open up for the national acts’ tours that would come through,” he said, adding that the exposure helped Digital Underground land opening slots for Rob Base and DJ E-Z Rock, Tone Loc, and others.

A friend of Chopmaster J’s who worked at the famed Berkeley record store Leopold Records sent Digital Underground’s demo to a friend who was interning at Tommy Boy. De La Soul, who was on that label, heard the demo and loved it, so Tommy Boy signed Digital Underground to record “Doowutchyalike” in 1989.

By that time, Too Short had already been signed to a major deal with Jive Records—based on buzz stemming from his ability to sell 50,000 copies of his independently released 1987 album Born to Mack from the trunk of his car and with no radio promotion—and MC Hammer had signed with Capitol Records.

Davey D was a crucial voice in the efforts by community and college radio stations to promote Bay Area rap artists. He’s the cofounder of the Bay Area Hip Hop Coalition, one of the first hip-hop radio DJ collectives in the country. He says stations like the San Francisco–based KMEL predate other large, well-known ones, like New York’s Hot 97. “The whole genesis of pop stations going hip-hop comes out of the Bay Area, and it comes out of all of us who were doing those college radio shows,” he says.

Indeed, in 1987, a new program director came on at KMEL with plans to treat hip-hop, as Dan Charnas writes, “as if it were just another kind of pop music,” and recognize rap’s commercial potential and popularity across different audiences. And while KMEL played a lot of pop-leaning rap—Tone Loc, Vanilla Ice, Young MC—it also added to its playlists artists considered to be the gatekeepers of “real” hip-hop: Eric B & Rakim, Public Enemy, N.W.A, and Boogie Down Productions. KMEL was playing hip-hop at a time when most major metropolitan area radio stations still treated it as a stigmatized genre. And, of course, KMEL was also the first commercial radio station to play three of the major rap hits from 1990: “U Can’t Touch This,” “The Humpty Dance,” and “Short But Funky” (which, ironically, was a not-so-veiled diss track directed at MC Hammer’s pop-oriented style).

The very intentional promotion of local hip-hop by KMEL and members of the Bay Area Hip-Hop Coalition on college and community radio trickled down to the audience as well. It created a demand and aesthetic preference for local artists over some of the most revered names in hip-hop history. Davey D says, “When [Nas’s] album came out in 1994, you didn’t hear it bumping in the streets of East Oakland. … There were other sounds and flavors that groups of people wanted to hear.”

He remembers bringing KRS-One to a local record store when he was visiting the Bay Area in the early 1990s. He told the rapper he’d give him $20 for anyone who came in to buy his record. Sure enough, the customers were looking for local rapper Pooh-Man and other Oakland artists. “They’re like, ‘Oh yeah, man, good music. But let me get this local stuff.’” It’s not that they hated New York, Davey D continues, but rather that they knew Pooh-Man: “He’s from around my way, I’m gonna listen to him. Yeah, he’s referring to 83rd and MacArthur,” and making local references to things like sideshows.

Notwithstanding the stylistic differences between the albums that came out of Oakland in 1990, there are a few throughlines that stand out, notably the influence of funk music and the increasing reliance of R&B groups on hip-hop production. It was this merging of R&B and hip-hop that catapulted songs like “Feels Good,” “Lies” (both of which feature rapped vocals in their bridges), “Hold On,” and “You Don’t Have to Worry” to the top of the Billboard charts.

Although there wasn’t a concerted effort to put out five successful albums, Davey D says, there was “intentionality in terms of people repping the Bay. … Not L.A., but Oakland; not San Francisco, but Oakland.” In other words, these five acts were proud of their Oakland roots.

All these artists continued making records as the decade wore on, and En Vogue, the Tonies, and Hammer all had incredibly successful follow-up albums with Funky Divas, Sons of Soul, and Too Legit to Quit, respectively. But these albums were all released across the span of a few years. And, at least in hip-hop, L.A. became synonymous with the West Coast G-funk style once Dr. Dre released The Chronic in late 1992, introducing the world to Snoop Dogg. By then, Tupac had moved on from Digital Underground to a solo career, and from Oakland to L.A., where he would begin his meteoric rise.

For a brief period 30 years ago, Oakland was the center of black popular music. Of course, Oakland’s legacy of incredible musicianship hasn’t waned—Ledisi, Goapele, Kehlani, Keyshia Cole, and Zendaya are all native daughters, in addition to numerous rappers. Still, 1990 was a special moment and the legacies of these five albums and acts are still noticeable today: from Too Short’s street-savvy model of distribution to the many top-tier acts D’Wayne Wiggins and Raphael Saadiq have produced, including Destiny’s Child, D’Angelo, Alicia Keys, Erykah Badu, Mary J. Blige, and Solange Knowles.

Oakland will never be the center of the music industry, but what it’s contributed to black popular music is immeasurable.

Rebecca M. Bodenheimer, Oakland, California, is an ethnomusicologist who has conducted research in Cuba since 2004, examining the contemporary performance practices of rumba and a range of other Afro-Cuban folkloric and popular musical styles in the cities of Havana, Matanzas, and Santiago.