Posted July 31, 2020 from KQED News —

Earlier this summer, education advocates scored a major win in the California state Assembly.

Legislation passed requiring all California State University students to take courses in ethnic studies, including African American, Asian American, Latinx and Native American studies. Gov. Gavin Newsom is expected to sign the bill later this summer.

Bay Curious received a question about ethnic studies from 23-year-old Michael Viray: “I’ve heard from one of my professors of ethnic studies at UC Davis that there was actually a revolution in the Bay Area for an ethnic studies field. Is this true? And how did it happen?”

Viray minored in Asian American Studies, fascinated by coursework that revealed the history and contributions of Filipino Americans, Asian Americans and Latinx Americans.

“It’s not being taught in classrooms,” he said. “I didn't know my own history.”

Michael’s professor was right. Ethnic studies was born from a revolution that began at San Francisco State in 1968. How it happened, is a fascinating story.

The Origins of Black Activism on Campus

November of 1968 was a tumultuous time. The United States was 13 years into the Vietnam War, Martin Luther King Jr. had been assassinated and the Black Panther Party was demanding systemic change for Black communities plagued by poverty and police brutality.

“There were members of the Black Student Union who were also members of the Black Panther Party,” said Nesbit Crutchfield, who started his studies at San Francisco State as a business school student in 1967. Crutchfield — who considered himself an “aspiring revolutionary” — soon joined San Francisco State’s Black Student Union, the very first in the country.

“There were members of the Black Student Union who were also members of the Black Panther Party,” said Nesbit Crutchfield, who started his studies at San Francisco State as a business school student in 1967. Crutchfield — who considered himself an “aspiring revolutionary” — soon joined San Francisco State’s Black Student Union, the very first in the country.

“I felt very privileged to be a member of the Black Student Union,” Crutchfield said. “It was clear to me that the Black Student Union represented a very progressive energy and thought among Black students in the Bay Area.”

However, just a small percentage of Black students attended San Francisco State. Enrollment rates for minority students had dwindled down to just 4%, even though 70% of students in the San Francisco Unified School District were from minority backgrounds. Black students were just a fraction of that 4%. Crutchfield remembers it as a time when “white supremacy was the norm of the day.”

“It was very unusual to see Black people in any positive positions,” Crutchfield said. “As a Black person, you expected to be one of the very few Black people in any classroom, laboratory or auditorium. [The campus] was overwhelmingly white.”

Meanwhile, Black students were hungry to study their own history. The Black Student Union had been pushing the university to create a Black studies department for nearly three years, but administrators resisted the idea.

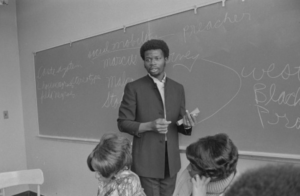

“Even though ethnic studies was not validated by the university, it doesn't mean that that study wasn't taking place,” said Jason Ferreira, a professor in the Department of Race and Resistance Studies at San Francisco State’s College of Ethnic Studies.

Ferreira has spent years collecting oral histories on the student strike. Back in 1968, he said, students had to create their own spaces to learn about their history.

“There was something called the Experimental College, which was a student-run initiative for them to teach their own classes,” Ferreira said. “The Black Student Union had its own classes, so that was another space.”

But students didn't just learn untold histories, they connected them to the ongoing struggle against systemic issues plaguing their communities, including poverty, police brutality and lack of affordable housing.

"It was an era of young people asking questions and wanting to transform their communities,” Ferreira explained. “That impulse, that hunger to transform one's community is actually what forms the basis of ethnic studies.”

Students of Color Create the Third World Liberation Front

In fall 1968, Penny Nakatsu — originally from San Francisco’s Western Addition neighborhood — was grappling with her own questions about race and identity. At San Francisco State, she pursued a self-directed degree in Asian American studies.

“We weren't ‘Asian Americans’ then, we were ‘Orientals,’ ” Nakatsu said. “ ‘Oriental’ is a term that was imposed on us by the larger society. Starting to use the term ‘Asian American’ was a way of taking back our own destiny.”

At San Francisco State, Nakatsu found herself gravitating toward people with like-minded values and who were involved in the anti-war movement. She became a member of a student organization called the Asian American Political Alliance, which was one of many ethnic student organizations on campus. In early Fall of 1968, these organizations banded together and formed a coalition called the Third World Liberation Front.

“At that particular time, ‘Third World’ referred to the nonaligned countries or cultures in Asia, Africa and Latin America,” Nakatsu explained.

Though students in the Third World Liberation Front came from different cultures, they believed they were united in their shared history of colonial and imperial oppression. The students saw parallels between their tension with the school and what they viewed as the oppression of the Vietnamese by the United States military.

The Firing of a Beloved Teacher Sparks Protest

One of San Francisco State’s most influential anti-Vietnam War organizers was a popular English instructor named George Mason Murray. He also happened to be the minister of education for the Black Panther Party. Students loved Murray, but his outspoken politics were not tolerated by San Francisco State administrators.

One of San Francisco State’s most influential anti-Vietnam War organizers was a popular English instructor named George Mason Murray. He also happened to be the minister of education for the Black Panther Party. Students loved Murray, but his outspoken politics were not tolerated by San Francisco State administrators.

“The war in Vietnam is racist,” Murray said in a televised press conference. “It is the war that crackers like Johnson are using Black soldiers and poor white soldiers and Mexican soldiers as dupes and fools to fight against people of color in Vietnam.”

The board of trustees forced San Francisco State’s president, Robert Smith, to fire Murray on Nov. 1, 1968. Five days later, the Black Student Union and the Third World Liberation Front joined together and went on strike.

Murray’s suspension was like setting fire to kindling.

Student strikers wanted the right to define their own educational experience. Together they drafted 15 demands, including a school of Third World studies, and a Black studies degree and department.

“In 1968, the vast majority of white people, a whole lot of Black people, and other people of color did not feel that it was reasonable to know more about themselves,” Crutchfield explained.

He disagreed. He and the other strikers felt it was vital.

“We knew that geniuses were falling by the wayside,” he said. “I’m talking about geniuses in education, in literature, in drama, in art ... geniuses, in politics.”

The strikers also wanted to raise admission rates for students of color. At the time, a special admissions program intended to prioritize marginalized students continued to allocate spots to white students. Meanwhile, the United States military was disproportionately drafting Black and brown men to fight in the Vietnam War. They weren’t eligible for student exemption if they weren’t in school, which meant that their right to an education was a matter of life or death.

Strikers vowed to boycott all classes until the school met their demands.

“We wanted to find out and be educated about ourselves,” Crutchfield said. “If we could not get that, then nobody could get an education.”

Five Months of Striking

Initially, strikers engaged in acts of disruption known as the “War of the Flea,” a campaign to disrupt the normal operations of the school. Students put cherry bombs in toilets and checked out huge quantities of books to overwhelm the school's library system.

Almost immediately, administrators invited police on campus. They swarmed San Francisco State, dressed in full riot gear and armed with five-foot batons. Students responded by throwing rocks and yelling obscenities at police and administrators.

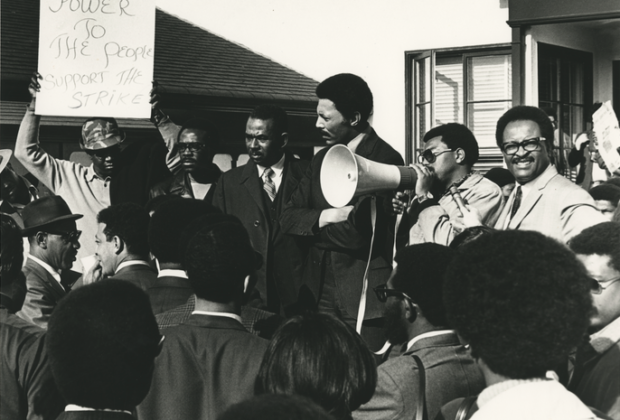

By this time, Crutchfield had become a leader of the strike, often speaking to huge crowds of protesters. He said his involvement put a target on his back.

“I'm quite sure they wouldn't have cared if some of us had died. They definitely wanted some of us to go to prison. Some of us went to prison,” he said.

One day early on in the strike, police surrounded the Black Student Union office. Crutchfield said police were looking to arrest its members.

One day early on in the strike, police surrounded the Black Student Union office. Crutchfield said police were looking to arrest its members.

“I volunteered to leave the Black Student Union first,” Crutchfield said. “The police started running at me. I got beat up with nightsticks and boots and fists.”

The police arrested Crutchfield and escorted him off campus. He faced charges for illegal assembly, resisting arrest and intent to injure and maim, resulting in more than a year in jail. At 80 years old, Crutchfield, now a mental health administrator in Richmond, said he is still dealing with the trauma of that time.

"I don't think you can talk to anyone who was at S.F. State, who participated [in the strike], who ran from the police and can say that they're the same person," he said.

He said he has no regrets.

“I was the great, great grandson of Africans who were made slaves,” he said. “I realized the things I got arrested for were really important to me.”

Many white students, especially white radicals, followed the lead of strike leaders like Crutchfield. They believed that without ethnic studies, they themselves had been denied a proper education. Their support intensified as the strike dragged on and the violence continued.

About a month into the strike, teachers joined with demands of their own. As tensions escalated, President Smith shut down the school indefinitely. However, Gov. Ronald Reagan and the California State University Board of Trustees demanded he reopen the campus. Smith resigned in December 1968.

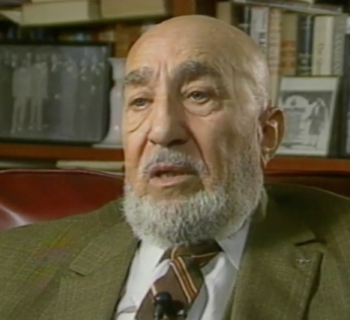

In his place, the board appointed S.I. Hayakawa, an English professor.

Hayakawa was popular with conservatives in Sacramento, but extremely unpopular with strikers. Their confrontations were heated and frequent.

Early on in his role as interim president, Hayakawa famously climbed aboard a sound truck and yanked the wires from a loud speaker during a student protest. Strikers, in return, called Hayakawa "The Puppet."

In early January, Hayakawa declared an end to student gatherings on campus. In a press conference he said he believed in the right to free speech, but that "freedom of speech does not mean freedom to incite riot."

The Mass Bust

Strikers ignored Hayakawa's ban on gatherings. Penny Nakatsu was protesting on Jan. 23, 1969 in what many call “the mass bust.”

"Two lines of police came up," Nakatsu said. "They surrounded over 500 people who were there for the rally and trapped all of the individuals who were caught within a human net."

Police charged at the students. Nakatsu said it was one of the bloodiest and most frightening days of the entire strike.

“The power of the state was trying to literally beat down the strike and strikers,” she said. “It was literally a practiced, orchestrated, military movement.”

Hundreds of protesters were arrested, backing up San Francisco's court system for months. Students, faculty and members of the community were affected, Nakatsu said.

“Many people suffered. Virtually all of the individuals who were arrested had to spend some jail time. A lot of those folks were blacklisted. University lecturers or teachers lost their jobs. There were real consequences to having participated in that event," she said.

Strikers Prevail

After two more months of striking, Hayakawa and strikers negotiated a deal on March 20, 1969.

The school agreed to accept virtually all nonwhite applicants for the fall 1969 semester, and establish a College of Ethnic Studies, the first in the country, with classes geared towards communities of color. Hayakawa gave Nakatsu and her peers the job of designing a curriculum from scratch in a matter of months.

"I have a feeling that one of the reasons why the administration agreed to that was I don't think they thought we could pull it off,” Nakatsu said.

The College of Ethnic Studies was ready by fall of 1969. Today, Nakatsu is a civil rights lawyer in San Francisco and believes in the importance of ethnic studies as much as ever.

“Ethnic studies is a way of embracing all of the cultures that make up the world,” she said. “If we don't understand each other, how are we going to get along? Ethnic studies is something that’s important, not just for people of color so we know about our histories and cultures and destinies, but for all people.”

Like many strikers, Ferreira believes ethnic studies should be required in K-12 schools, as well as universities.

“The demand for ethnic studies is as important today as it ever was, if not more,” he said. “The inability of this country to come to terms with the ongoing practices of racism and white supremacy speaks to the demands of the Third World Liberation Front and the Black Student Union for an education that was relevant and transformative. It's still an uphill battle. But we'll win."