Posted March 7, 2021 from CNN —

A woman who says she is the direct descendant of a man and woman pictured in some of the earliest known photographs of enslaved people does not have a property interest in the images, now owned by Harvard University, a Massachusetts judge ruled Tuesday.

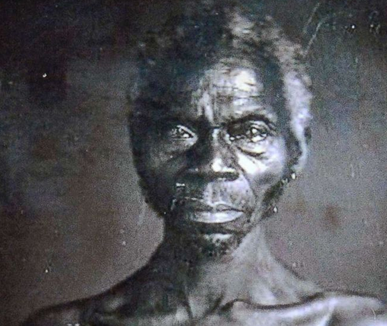

Tamara Lanier, 58, took Harvard to court in March 2019 for "wrongful seizure, possession and expropriation" of the images, arguing her great-great-great grandfather Renty and his daughter Delia "remain enslaved" by the university.

"Fully acknowledging the continuing impact slavery has had in the United States, the law as it currently stands, does not confer a property interest to the subject of a photograph regardless of how objectionable the photograph's origins may be," Justice Camille Sarrouf wrote in an order dismissing the case in Middlesex County Superior Court.

It is a "basic tenet of common law" that a photograph's subject has no interest in a negative, nor any photographs printed from the negative, Sarrouf wrote in the 15-page ruling, adding that the court is constrained by "current legal principles," and only the state legislature or appellate courts can "provide the redress Lanier now seeks."

Lanier's lawsuit claimed Harvard profits off the images and asked that the university turn them over and pay unspecified damages. The images are believed to be the earliest known photographs of slaves. One was used in 2017 as a cover photo for the book "From Site to Sight: Anthropology, Photography and the Power of Imagery."

According to the lawsuit, the daguerreotypes -- an early type of photo produced on a silver or silver-covered copper plate -- were commissioned in 1850 by Harvard professor Louis Agassiz, who espoused a theory that Africans and African Americans were inferior to White people.

After being named head of Harvard's newly created Lawrence School of Science, Agassiz became an advocate for polygenism -- the idea that humans evolved from multiple distinct ancestral types and that the suit said was used to justify the enslavement of Black people and, later, their segregation.

According to Lanier's complaint, the images offered "celebrity status and 'scientific' legitimacy to the poisonous myth of white racial superiority and championing the vital importance of separations of races."

More than 40 of Agassiz's direct descendants signed a letter saying "it is time for Harvard to recognize Renty and Delia as people" and return the images to Lanier.

Harvard did not dispute Lanier's ancestral claim in its motion to dismiss the case, arguing instead her claims are barred by the statute of limitations, and that she has neither a property interest nor legal standing.

Lanier told CNN on Friday that she will appeal the ruling, calling Harvard's legal arguments "unjust and inhumane on so many levels." The case, she said, is not simply a dispute between a photographer and his subjects, but centers on "the plunders of slavery."

Renty and Delia are victims of a crime, she said.

"I think that Harvard, just how they have treated not only Renty, but his family, his legacy, his rich cultural history -- it's confirmation that they devalue Black lives," Lanier said, adding that she hopes Harvard will still "do the right thing" given its past statements supporting the Black Lives Matter movement.

"At this point I think Harvard is exposed for their hypocrisy on their ties with slavery and how they've come to reckon with it," Lanier said.

CNN has reached out to Harvard University for comment.

The university told the New York Times in a statement that the images were "powerful visual indictments of the horrific institution of slavery," and it hoped the ruling would help make the photos more accessible to the public going forward.