From The Katy Trail Weekly —

By David Mullen —

My next-door neighbor growing up in Oakland was a short, Italian man named Frank Russo, a wealth of information on Pacific Coast League history that included Joe DiMaggio (a San Francisco-native who had two baseball-playing brothers Dom and Vince) of the San Francisco Seals, Ernie Lombardi, Casey Stengel and Billy Martin of the Oakland Oaks and a variety of other great players and managers that played up and down the coast. An avid cigar chewer, Russo would bring out his collection of cigarette cards to support his stories.

New to the other side of my house was Tom Teal. The sound of the cue ball hitting the rack in his garage pool table one night was all I needed to come over, introduce myself and become fast friends. He was a big, strong African American man and a football fan. I was a short, husky 10-year-old and a baseball junkie. We were definitely an odd match. Teal was a transplant from Beaumont and spoke nostalgically of the football greats from his area like Jerry LeVias and Bubba Smith, to name a few.

New to the other side of my house was Tom Teal. The sound of the cue ball hitting the rack in his garage pool table one night was all I needed to come over, introduce myself and become fast friends. He was a big, strong African American man and a football fan. I was a short, husky 10-year-old and a baseball junkie. We were definitely an odd match. Teal was a transplant from Beaumont and spoke nostalgically of the football greats from his area like Jerry LeVias and Bubba Smith, to name a few.

I could come back with tales I had heard of basketball stars like Bill Russell and Paul Silas and football names like John Brodie, Chris Burford and MacArthur Lane, all who grew up in Oakland. But when it came to baseball, no one could top me, not even the towering Teal.

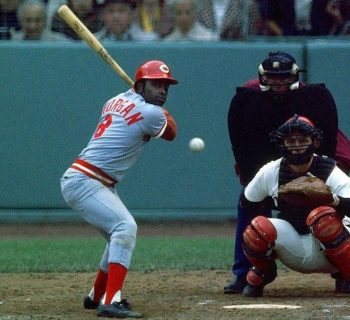

The city was full of stories of legends. Hall of Famers Frank Robinson, Joe Morgan and Willie Stargell (who lived in nearby Alameda) all grew up on the ball fields of Oakland. Vada Pinson, in the Cincinnati Reds Hall of Fame, was a Gold Glove Award winner and a four-time All-Star.

Later, when I was a senior in high school, the All-City All-Star outfield was comprised of Hall of Famer Rickey Henderson, five-time Gold Glover and former Texas Ranger Gary Pettis and Toronto Blue Jays All-Star Lloyd Moseby. Yes, we knew our baseball in the East Bay.

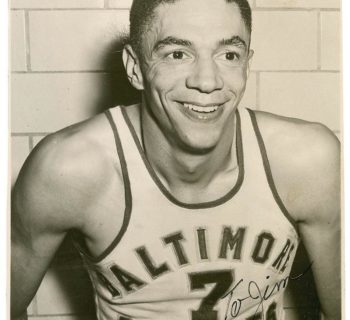

Often lost in the lore of Oakland baseball greatness was a player that arguably had a bigger impact on the game than any of the Hall of Famers or All-Stars. He was Curt Flood, who shared the outfield with Robinson and Pinson at McClymonds High School. Robinson, Pinson and Flood all signed with the Reds organization out of high school.

With Pinson on the way to the big leagues from the Reds farm system, Flood was traded to the St. Louis Cardinals in December 1957. In St. Louis, he won two World Championships, was a three-time All-Star and a seven-time Gold Glove winner. His defensive prowess in the 1960s put him in the same conversation with the legendary Willie Mays.

But 50 years ago, Flood did the unthinkable. He challenged baseball's reserve clause after refusing to accept a trade following the 1969 season. Although his plea was unsuccessful, despite being heard all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, it changed the way that players and owners negotiated contracts.

In a blockbuster trade following the 1969 season, the Cardinals traded Flood with Tim McCarver, Byron Browne and Joe Hoerner to the Philadelphia Phillies for Dick Allen, Cookie Rojas and Jerry Johnson. Flood refused to join Philadelphia, citing a team and a stadium in disrepair and a reputation for racist fans.

In a letter to baseball commissioner Bowie Kuhn, Flood wrote, “After 12 years in the major leagues, I do not feel I am a piece of property to be bought and sold irrespective of my wishes. I believe that any system which produces that result violates my basic rights as a citizen and is inconsistent with the laws of the U.S.”

In Flood v. Kuhn (407 U.S. 258), through his attorney, Flood maintained that the reserve clause depressed wages and limited players to one team for life. Not known as activist, Flood reportedly told the executive board of the baseball players' union, “I think the change in black consciousness in recent years has made me more sensitive to injustice in every area of my life.”

Years later and inspired by Flood, executive director of the Major League Baseball Players Association Marvin Miller transformed the union into a piller of strength, allowing players the right to free agency and limiting the amount of years a player can be with one team before becoming eligible for salary arbitration. The most Flood earned as a Cardinal was $90,000 (approximately $600,000 today). The average MLB player in 2020 makes more than $4.3 million.

Years later and inspired by Flood, executive director of the Major League Baseball Players Association Marvin Miller transformed the union into a piller of strength, allowing players the right to free agency and limiting the amount of years a player can be with one team before becoming eligible for salary arbitration. The most Flood earned as a Cardinal was $90,000 (approximately $600,000 today). The average MLB player in 2020 makes more than $4.3 million.

Miller will be inducted, posthumously, into the Baseball Hall of Fame in July. Flood, who died in 1997 and was blackballed after challenging baseball's archaic labor laws, is not in the Hall of Fame.

In honor of the 50th anniversary of Flood's stand for right and wrong, Flood's widow Judy and members of Congress are championing the cause for his enshrinement, according to reports. His recognition is long overdue.

It is time to open the gates at Cooperstown and put Flood into Baseball's Hall of Fame. Not just because he was a game changer on the field, but because he changed the game off the field. Every current player that visits Cooperstown, including those who grew up playing ball on the streets of Oakland, should be able to tip their cap and thank him for his stand against baseball inequality. They owe it to him, in more ways than one.