Posted September 7, 2020 from Tidal —

There’s a young man, Aidan Levy, who is writing a biography on you. How are you going to feel reading about your own life?

I don’t know. I’ve met him, but I don’t really know him. I haven’t read anything and don’t know what he’s going to write. Being a public figure, I’m ready for whatever he writes. But I’m not looking forward to it. [laughs]

Looking at the positive side, hopefully it will bring back some good memories. But you’ve been known to not read reviews of your work.

Well, everyone says that they’re not going to read reviews of their work, but it’s hard not to read them.

You famously said that if you’re going to believe the good stuff, you’re going to have to believe the bad stuff, because sometimes you’re praised when you know you’re not at your best.

Do you know that book Lexicon of Musical Invective by Nicolas Slonimsky? He was a musician and conductor and he wrote this wonderful book for artists to read because he researched the reviews that famous composers received. It’s a great book because you see that when something like the William Tell Overture came out, the reviewer said it was terrible. It’s important for artists to read that book, because when you get torn down, you won’t feel so bad. You can blame it on the reviewer.

But I can also appreciate Cocteau’s recommendation to artists: “What the public criticizes in you, cultivate. It is you.” Maybe what you’re being criticized for is who you are, so why not own it?

That’s beautiful. But it’s hard for people to face up to the negative parts of themselves. I hate to read negative reviews of my work, but I do think, “Let me take this in and change it.” I never admit that I’m doing that, but I’m always trying to improve.

There’s a young man, Aidan Levy, who is writing a biography on you. How are you going to feel reading about your own life?

I don’t know. I’ve met him, but I don’t really know him. I haven’t read anything and don’t know what he’s going to write. Being a public figure, I’m ready for whatever he writes. But I’m not looking forward to it. [laughs]

Looking at the positive side, hopefully it will bring back some good memories. But you’ve been known to not read reviews of your work.

Well, everyone says that they’re not going to read reviews of their work, but it’s hard not to read them.

You famously said that if you’re going to believe the good stuff, you’re going to have to believe the bad stuff, because sometimes you’re praised when you know you’re not at your best.

Do you know that book Lexicon of Musical Invective by Nicolas Slonimsky? He was a musician and conductor and he wrote this wonderful book for artists to read because he researched the reviews that famous composers received. It’s a great book because you see that when something like the William Tell Overture came out, the reviewer said it was terrible. It’s important for artists to read that book, because when you get torn down, you won’t feel so bad. You can blame it on the reviewer.

But I can also appreciate Cocteau’s recommendation to artists: “What the public criticizes in you, cultivate. It is you.” Maybe what you’re being criticized for is who you are, so why not own it?

That’s beautiful. But it’s hard for people to face up to the negative parts of themselves. I hate to read negative reviews of my work, but I do think, “Let me take this in and change it.” I never admit that I’m doing that, but I’m always trying to improve.

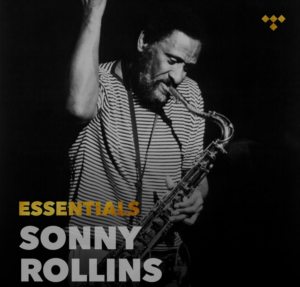

Arguably the greatest living jazz musician, Sonny Rollins turned 90 on Sept. 7, 2020. The legendary tenor saxophonist was forced to stop performing in 2012, because of a respiratory problem he believes was exacerbated if not created by toxic fumes in the aftermath of 9/11. Rollins was living in an apartment not far from the Twin Towers and was forced to evacuate his building amidst the debris and pollution. He went to Boston, where four days later he gave a concert that was eventually released as the Grammy-winning Without a Song: The 9/11 Concert album. That’s just one of the many inspirational and nearly apocryphal stories about Rollins. Perhaps the most famous tale concerns his taking a hiatus from gigging and recording in 1959 to improve himself, and then going out from his apartment on the Lower East Side of Manhattan to practice on a pedestrian walkway of the Williamsburg Bridge.

With the passing of his wife and manager Lucille in 2004, Rollins now lives alone in upstate New York, listening to sports (mostly baseball, as a recovering Mets fan) and news on the radio, reading voraciously and practicing yoga. Minus the opportunity to play his horn, he’s become increasingly devoted to his own spiritual development.

Known for his very critical ear toward his performances on record, he has given his blessing to the release of a collection of live and studio recordings from Holland in 1967, when he toured and appeared with bassist Rudolph “Ruud” Jacobs and drummer Han Bennink. Slated for a limited-edition vinyl release Nov. 27 on Resonance Records, with additional formats to follow, Rollins in Holland features the saxophonist at the peak of his powers, playing with his signature fiery brand of rhythm, intensity and humor.

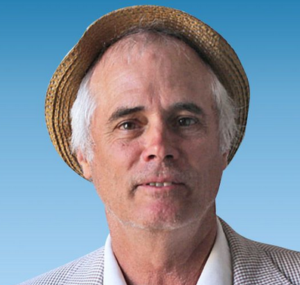

Sonny and I have been friendly since the early ’90s, when I first contacted him for coverage in JazzTimes, a publication I oversaw for nearly three decades. In the ensuing years, we’d talk on the phone or exchange letters — yes, letters in the mail — though the subject was most often baseball or politics rather than music. In this recent freewheeling talk for TIDAL, he shared his thoughts and memories of those ’67 recordings, of his colleague John Coltrane (with whom he famously “battled” on “Tenor Madness”) and of growing up in the Sugar Hill section of Harlem.

Sonny and I have been friendly since the early ’90s, when I first contacted him for coverage in JazzTimes, a publication I oversaw for nearly three decades. In the ensuing years, we’d talk on the phone or exchange letters — yes, letters in the mail — though the subject was most often baseball or politics rather than music. In this recent freewheeling talk for TIDAL, he shared his thoughts and memories of those ’67 recordings, of his colleague John Coltrane (with whom he famously “battled” on “Tenor Madness”) and of growing up in the Sugar Hill section of Harlem.

Although a very politically aware individual who in 1958 recorded “The Freedom Suite,” a remarkably prescient expression of support for the civil-rights movement, in this case Rollins was in a more reflective mood and preferred not to talk about the state of the country in detail. Rather, he wanted to explain his philosophy of life, which is greatly influenced by Eastern religion and spirituality. In the end, he did wonder how far Donald J. Trump would get if he counted back from 100.

Good news for you and me, baseball is back, though who knows for how long.

I’m happy about that, but I don’t want guys to get hurt or sick just because I want to see some baseball. And I don’t want guys to get hurt just because these rich owners want to make more money.

Growing up in Sugar Hill, did you go to Yankee Stadium in the Bronx?

Yes, I lived closer to the Polo Grounds, where the Giants played, but I went to Yankee Stadium because my team was the Yankees.

Where was the Polo Grounds?

It was on the Manhattan side, very close to me, about six or eight blocks north of us and down the hill on Eighth Avenue. I could walk there. I used to go to [popular swing musician and bandleader] Andy Kirk’s house. His son was a good friend of ours, so we’d go to his house and we could see right field of the Polo Grounds. I used to see Carl Hubbell, the great pitcher who struck out the famous hitters.

Famous for his screwball. My father lived at 6th & Lehigh in Philadelphia, and when he was a kid, he and his friends would walk the 15 blocks to 21st & Lehigh and stand with their gloves outside Shibe Park, behind home plate, and wait for foul balls to come back over the roof. That was a day’s entertainment. I miss the days when ballparks were right in neighborhoods, and the players often lived in our neighborhoods. Did any live near you?

Willie Mays lived around the corner when he was playing with the [New York] Giants. He could walk to work, really.

Did you play stickball or baseball?

I played stickball and softball. We used to go to Yankee Stadium and there were ballfields outside the stadium, so we’d play softball there. Other than that I played stickball on the streets.

The New York City game.

It was great. I’ll never forget one particular homerun.

Did it go through a window?

[laughs] No, it just went a long way. Several houses up and over the roof. I’ll never forget it, man. We lived on a block with houses on one side and the other side was a park going down. But that one side, I always wondered what would happen if we ever hit one and broke a window. But it never happened that I remember. Everybody loved baseball then. The people watched us from the windows. A lot of the older guys got a kick out of watching us play.

What was the ball in stickball? Was it a bunch of tape, balled up? I think we used what we called a pimple ball.

It was a rubber Spaldeen, usually a red color. A little smaller than a regular baseball.

Sugar Hill was quite a neighborhood to grow up in.

I was very fortunate to grow up there. We had a lot of musicians, a lot of great political people, the Black intelligentsia. That’s why they called it Sugar Hill, because it was for people who could afford it in the Black community. I was born down the hill but we moved up to Sugar Hill. It was a more affluent community. We didn’t live in one of those affluent buildings, but they were all close by, on the block.

Jackie McLean was there. There was a great young trumpeter [Lowell Lewis] who didn’t go anywhere. A lot of us got messed up with drugs after a while. [Saxophonist] Andy Kirk Jr. was part of the neighborhood. Arthur Taylor was there and we played together. The pianist Kenny Drew lived down the hill but he would hang with us.

Let’s talk about this new album of old material. In reading the notes to this album of trio performances in Holland in 1967, I was surprised at how positive you were about it. You’re usually so critical of your own playing in the past.

Actually, there was another record they wanted me to put out, another archival one that was around the time of The Bridge. It was an earlier one, when I was just coming back from the bridge and just returning to playing. That would have been more incentive or [of more] interest for people.

But even though the guys weren’t ones we’d know from the United States, the one from Holland had more verve and energy. I decided that. With the other one, coming back from the bridge, the band wasn’t there yet. We later did albums with that band that were about the best, with Jim Hall, Ben Riley and Bob Cranshaw. These were earlier things that they wanted me to release, which would have been more enticing for people to listen to, but it didn’t have that energy. There was a lot of romance coming back from the bridge and the places we started playing at on the East Side. It was a nice romantic story, but the music wasn’t as energetic as this one in Holland. I had to fight for them to accept that.

During the time of your hiatus, you were speaking regularly with John Coltrane.

I first played with Trane around 1948 or so, after I graduated from high school, with Miles and Kenny Clarke.

You stayed friends with him all your life. Sometimes people assume that jazz musicians are rivals, but Trane was a great colleague for you.

There is a certain element of competition in music, but between people that respected each other, it mitigates that. People want that competition or that element. But Trane liked me and I loved him. We had great admiration and respect for each other, which was great because we remained close friends. He used to come to my house and we shared music, but we did a lot of other things as friends. We remained close until his passing.

Do you know his son Ravi?

I think he’s a great musician. Usually a guy who is the son of somebody like Coltrane, you wouldn’t expect them to be as good. But he really got better and better, and now he’s a first-class musician.

During that period both you and Trane were immersing yourself in Indian music and spirituality. Is that something you shared?

Oh yeah. We used to talk about that a lot. We used to exchange books about spirituality. We talked about Buddhism and religion. He was a close friend. In fact, a guy is writing a book about Blindfold Tests [a jazz-magazine exercise that involves musicians listening to and commenting on music without seeing the album cover or liner notes prior] and I had to go back and read some of the things I said in those. And back then I said that Coltrane was not only a great musician but he was a great human being. That was testament to our relationship. Looking back at what I said, I feel much of the same things today. I had a lot of respect for the music and for the individuals I liked then and I like now. I’m glad I didn’t have a different attitude about music or life than what I have now.

You don’t seem to have any competitiveness or bitterness or negativity.

I’m glad I didn’t say anything negative.

When you went to the ashram in India in 1967, was it just for the spiritual learning or were you also studying Indian music? We all heard that influence in Trane’s music, but we don’t hear it much with yours.

I don’t know if my music changed because of my time in India. I did write a song while I was there that we recorded later for Milestone. I went there for the spiritual education. I took my horn with me, naturally, and I did play with a guy there at the ashram, where one day we played a little concert for the people.

What did he play?

He played the nadaswaram; it’s like a big oboe. We just played. I went over there mainly to study yoga.

That’s been a foundation of your life ever since.

Oh yeah. I’m deeply into Eastern religion. Around the mid-’50s is when I started reading about these religious things, specifically Eastern religion.

Does that account for your belief in reincarnation?

Absolutely. Reincarnation makes a lot of sense in this world. It’s not just one trip. We can’t learn it all in one trip. A lot of people confuse you with your body. My body is going to turn into dust just like everything else on this planet. It’s not about my body — it’s about my spirit, my soul. My body is going to be in a funeral home. That’s not me. Once I pass on, I leave that body. Then I’m looking for another body, and then I can continue my journey and learn what this beautiful universe is all about. It takes a long time. You reap what you sow. It takes a long time to realize that you have to be a good human being. Who knows how many trillion lives I’ve lived. I know that you can’t get it in one life. Not enough time.

There’s so much to contemplate, so much to get right and understand. A lot of foolish things I’ve done, I have to learn from that so next time I’m not going to do that. It takes a while to perfect your soul. In Buddhism, that’s what it’s all about. With each incarnation you’re getting more and more information, and understanding the universe and about relationships with other people. Here I am, 90 years old, and my knowledge gets better. And you’re right — 90 came pretty fast.

And so many great artists died so young, like Coltrane and Wes Montgomery.

Charlie Parker was just 34 when he died. His creative thing was fantastic, but knowing Charlie Parker, his soul was ready to come back and reincarnate, because he had a lot of things he did in his life that he regretted. One thing was using drugs and then getting younger acolytes like myself to follow him. That was one of the things that killed him.

That he felt responsible for young people like you who thought drugs were part of being a creative jazz musician?

Yes, absolutely. I know that for a fact. He’ll have other times in the development of his soul until he gets to that point where it’s all good. And Trane was young too, 40, when he died.

I understood from reading the liner notes to the Rollins in Holland set that during your final conversations with Trane, you got a sense that he was ill even though he didn’t mention his condition [liver cancer].

Yes, we used to talk on the telephone. The last time I talked to Coltrane his voice had a musical overtone. You know what overtones are: Every note is not just one note but consists of a lot of other notes. I could hear that in the sound of his voice. I didn’t say anything about it. Coltrane was a beautiful human being.

He certainly had a challenging path. He developed himself musically but also personally and spiritually.

That’s right. Exactly. That’s what I’m trying to do: go through things and find a spiritual answer in life. Get out of it in a more wise position.

Do you go over your past mistakes?

I’ve made some terrible mistakes, and that’s OK. I pray all the time for forgiveness for some of the things I did in my life.

Even now?

Sure, because it happened some years ago, but it did happen. And I did some ignorant and stupid things that I shouldn’t have done. I’m sure I hurt people. I know I did. I did things I need to ask forgiveness for. It makes me feel that I’m cleaning it up a little bit. And I pray to some of the people I’ve hurt in my life.

Your wife Lucille was such an important person in your life. How does she figure into all of this?

I don’t know that our spirits will reconnect. It’s possible that we’ll meet again in another realm. In lieu of that, I pray to Lucille for some things I did wrong to her. Maybe I’ll see her in another realm, but I don’t know. In praying I conjure her and other people. I can almost see them as I knew them, and there’s a closeness there.

Yes, it’s wonderful. That’s a blessing. My mother came back to me after she passed away and it was such a great day. I woke up and I was in tears because I was sort of arguing with her before she passed. When she died suddenly, and I wasn’t there, I really felt guilty. But she came back to me in sort of a dream while I was sleeping. But it was more than a dream. She came back and talked to me.

Going back to the recording, I understand that you used different horns than usual.

Right, I used a couple of horns on that. One of the horns was one I borrowed from a Dutch musician, Jos van Heuverzwijn, who passed away. His wife was kind to give me that horn.

Did you feel his spirit with the horn?

Everything happens for a reason. There’s nothing random in the world, because there is an all-seeing eye. You can’t fool anybody. … Everything I do, I do for a reason. I found out why, now or later. The reason we’re here is to improve our spirit and soul until we can reach our particular God, whatever we think that is.

Have there been people in your life who you think are far along spiritually?

Absolutely. People we know who have lived and developed as human beings, sure. We’re all trying to develop as we go through our lives. That’s why it’s not about one life. Some people are further along on their journey than other people are. Someone is further along than I am; I’m further along than someone else. We’re all on our separate journeys. It’s all justice. People can’t get away with anything.

But with all the horrible news and events out there, I can’t help but wonder.

People tell me what a terrible world this is with Trump and the police and wars and disease. You know what I tell them? The world has always been a terrible place. It’s no different now. Cain killed Abel in the Bible. He killed his brother. The world is always going to be a place of ignorance and hatred. That’s the world. What’s supposed to change is Sonny Rollins or Lee Mergner. We’re supposed to change as we go through what we did that was wrong. You’re going to reap what you sow. The universe is justice. It’s very different than man-made justice.

It’s the simple concept of karma.

Yes, exactly. Karma is simply what goes around comes around.

Can you give an example of someone you met that you feel is further along spiritually? Can you sense that?

Oh sure. I could say Coltrane.

When I was growing up with the group of guys who lived on the block, this one guy was the son of the superintendent of the building we lived in. He was the oldest son. In those days we had coal burning for heat and you had to clean out the ashes afterward. I used to watch this guy and think, “Wow, he has this calm personality and he’s a really together person.” He was a guy who didn’t mind doing it and did it like it was his duty. I always admired that guy. I don’t think you can get that. You bring it with you when you’re born. We all do. It’s not my business to wonder how many lives it takes. My business and our business as human beings is to make this life right, to do the best I can in this life. It’s all good, man. I want to advance and learn more. It’s all a beautiful experience.

I’m mostly agonizing over my playing. There’s a lot of “I wish I had done that.” It’s good and bad.

What was the good?

I think I was young and very sure of certain things musically and otherwise. I think I was born with certain attributes. Looking back, I had some good attributes. I think I was a good guy in many ways. I can look back and know that I wasn’t the worst person in the world.

There’s a young man, Aidan Levy, who is writing a biography on you. How are you going to feel reading about your own life?

I don’t know. I’ve met him, but I don’t really know him. I haven’t read anything and don’t know what he’s going to write. Being a public figure, I’m ready for whatever he writes. But I’m not looking forward to it. [laughs]

Looking at the positive side, hopefully it will bring back some good memories. But you’ve been known to not read reviews of your work.

Well, everyone says that they’re not going to read reviews of their work, but it’s hard not to read them.

You famously said that if you’re going to believe the good stuff, you’re going to have to believe the bad stuff, because sometimes you’re praised when you know you’re not at your best.

Do you know that book Lexicon of Musical Invective by Nicolas Slonimsky? He was a musician and conductor and he wrote this wonderful book for artists to read because he researched the reviews that famous composers received. It’s a great book because you see that when something like the William Tell Overture came out, the reviewer said it was terrible. It’s important for artists to read that book, because when you get torn down, you won’t feel so bad. You can blame it on the reviewer.

But I can also appreciate Cocteau’s recommendation to artists: “What the public criticizes in you, cultivate. It is you.” Maybe what you’re being criticized for is who you are, so why not own it?

That’s beautiful. But it’s hard for people to face up to the negative parts of themselves. I hate to read negative reviews of my work, but I do think, “Let me take this in and change it.” I never admit that I’m doing that, but I’m always trying to improve.