Posted February 9, 2020 from The New Yorker —

Some of the best offerings in 2016 New York Film Festival were documentaries. The festival opened with Ava DuVernay’s powerfully and passionately insightful documentary “13th,” a brilliant analysis of the historical roots of the politics behind today’s scourge of mass incarceration. Then, on Sunday and Monday, the festival showed the Swedish director Kasper Collin’s “I Called Him Morgan,” centered on the relationship between the great trumpeter Lee Morgan and his common-law wife, Helen Morgan, who shot him to death, in a Lower East Side jazz club, in 1972.

The backbone of Collin’s film is the sole audio interview with Helen Morgan, made in 1996, shortly before her death. The story that she tells combines with the story that Collin builds around it to provide a revelatory and moving portrait of a great musician and the other great people, whether celebrated (like musicians with whom Lee Morgan performed) or unheralded (like Helen), on whom his art and his life depended. It’s both a portrait of people and a historical landscape, a virtual vision of American times—the lives of black Americans in the age of Jim Crow and de-facto discrimination in the North—and of the artistry and personal style that arose in response to them.

The backbone of Collin’s film is the sole audio interview with Helen Morgan, made in 1996, shortly before her death. The story that she tells combines with the story that Collin builds around it to provide a revelatory and moving portrait of a great musician and the other great people, whether celebrated (like musicians with whom Lee Morgan performed) or unheralded (like Helen), on whom his art and his life depended. It’s both a portrait of people and a historical landscape, a virtual vision of American times—the lives of black Americans in the age of Jim Crow and de-facto discrimination in the North—and of the artistry and personal style that arose in response to them.

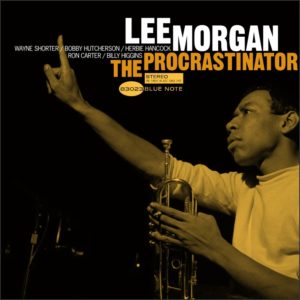

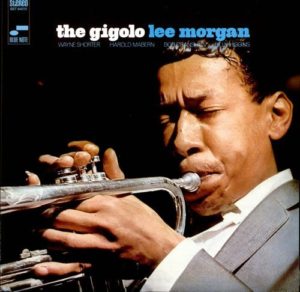

Helen Morgan, born in 1926, had a hard youth in North Carolina and came to New York in the nineteen-forties, while still a teen-ager, to try to make her own way. She worked as a telephone operator, frequented jazz clubs, and became a sort of local celebrity, turning her home, in Hell’s Kitchen, into a virtual salon where artists and free spirits gathered. Meanwhile, Lee Morgan, born in 1938, was a brilliant young trumpet star, already a celebrated artist as a teen-ager. (He recorded his first album, leading his own band for the trailblazing Blue Note label, at the age of eighteen.) By 1960, he had recorded with John Coltrane, Dizzy Gillespie, Tina Brooks, Sonny Clark, and Wayne Shorter, and was a member of Art Blakey’s group, one of the most popular and forward-looking (a rare combination) of the time. (Shorter joined that band, too—Blakey was one of the great talent scouts of the jazz world.)

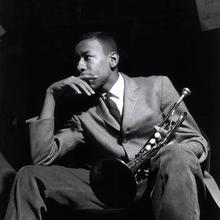

In interviews with leading musicians of the era who knew and performed with Lee Morgan, such as Shorter, the drummers Albert (Tootie) Heath and Charli Persip, and the bassists Paul West and Jymie Merritt, Collin brings out stories of the fast life that went with the night life of jazz—fast cars, sexual adventures, fine clothing. Persip talks about racing his Austin-Healey against Morgan’s Triumph; Heath mentions speeding late at night through Central Park. Shorter speaks of performing in night clubs and drinking double or triple cognacs between sets: “I would drink and have like a thin veil around me—that’s my space, my little dream space—and we would play.”

In interviews with leading musicians of the era who knew and performed with Lee Morgan, such as Shorter, the drummers Albert (Tootie) Heath and Charli Persip, and the bassists Paul West and Jymie Merritt, Collin brings out stories of the fast life that went with the night life of jazz—fast cars, sexual adventures, fine clothing. Persip talks about racing his Austin-Healey against Morgan’s Triumph; Heath mentions speeding late at night through Central Park. Shorter speaks of performing in night clubs and drinking double or triple cognacs between sets: “I would drink and have like a thin veil around me—that’s my space, my little dream space—and we would play.”

There were also drugs, and Morgan became addicted to heroin. Quickly, Morgan had practical troubles as a result. Morgan became unreliable and left Blakey’s band; he also hurt himself seriously, nodding out beside a radiator and burning the side of his head, giving himself a bald spot and a scar as a result, which he concealed with a sort of comb-over for the rest of his life. Shorter, who was close with Morgan, felt that he was slipping away; in the film, looking at a photo of Morgan with his head bandaged, he talks to the photo—“What you doing, man? Lee, what you doing?” Morgan pawned his clothing to buy drugs; Heath recalls Morgan saying that he’d prefer to get high rather than play music. Morgan couldn’t get work—and then he met Helen Morgan at her apartment, and she made him her project. She helped him get off drugs, she helped him get his career back together, she took care of the practical aspects of his work—and he was playing more daringly than ever. Then he started to see another woman—Judith Johnson, who discusses their relationship in the film—and the ultimate result was the violent showdown in Slug’s, on East Third Street.

Collin’s film brings out these stories with a wealth of details energized by the experiences and the insights of his interview subjects as well as an engaging range of archival images and clips. Some performances by Lee Morgan are also highlighted on the soundtrack, but, of course, in a ninety-minute film, it’s inevitably the music itself that gets shortest shrift. That’s no knock on the film but, rather, a reason to do some listening apart from it. So I’ve put together a playlist that goes through Morgan’s recording career, from the beginning through his live 1970 set at the Lighthouse, in Hermosa Beach, California.

Morgan’s style of hard bop, a style launched by Blakey, Miles Davis, Horace Silver, and others in the mid-nineteen-fifties, was a kind of simplification of bebop—an infusion of blues in the place of some of bop’s harmonic complexity. The result was a musical paradox—on the one hand, some of the music (such as Blakey’s and Silver’s) leaned toward popularity, without musical compromise. On the other, the simplifications opened a new and freer kind of musical space for soloists, pulling other hard-boppers (such as Davis and Jackie McLean) in the direction of the avant-garde and free jazz. Morgan’s own career moved in both directions—he played often with Blakey—and he also played frequently with McLean, as well as with Bobby Hutcherson, Andrew Hill, and other progressive luminaries of the nineteen-sixties. Both of those tendencies are represented on this list—sometimes in the very same performance.

Morgan’s style of hard bop, a style launched by Blakey, Miles Davis, Horace Silver, and others in the mid-nineteen-fifties, was a kind of simplification of bebop—an infusion of blues in the place of some of bop’s harmonic complexity. The result was a musical paradox—on the one hand, some of the music (such as Blakey’s and Silver’s) leaned toward popularity, without musical compromise. On the other, the simplifications opened a new and freer kind of musical space for soloists, pulling other hard-boppers (such as Davis and Jackie McLean) in the direction of the avant-garde and free jazz. Morgan’s own career moved in both directions—he played often with Blakey—and he also played frequently with McLean, as well as with Bobby Hutcherson, Andrew Hill, and other progressive luminaries of the nineteen-sixties. Both of those tendencies are represented on this list—sometimes in the very same performance.

Also, here are a few live performances that aren’t available on Spotify; the one from 1968, of Thelonious Monk’s “Straight, No Chaser,” is among my very favorites:

Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers, 1958.

Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers, 1965.

Lee Morgan and Clifford Jordan, 1968.

Lee Morgan, San Francisco, 1970.

Richard Brody began writing for The New Yorker in 1999. He writes about movies in his blog, The Front Row. He is the author of “Everything Is Cinema: The Working Life of Jean-Luc Godard.”