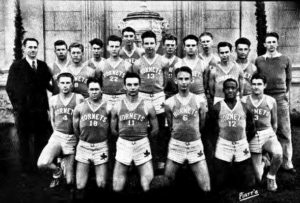

Herman Pete was a star student athlete in the 1930's, first at Alameda High School and then later at Marin Junior College, excelling in both football and baseball.

Pete attended high school and college at a time when only a small quota of African-American athletes were allowed to play on American college sports teams such as at the University of California at Berkeley, and were banned altogether from professional sports. But Pete was so popular among his fellow athletes at Alameda High—almost all of them white—that he was elected president of the school's Block A honor athletic society for the spring, 1933 term.

According to the January 15, 1933 issue of the Oakland Tribune, "The Block A Society is composed of students who excel in athletics and Pete [is] a star athlete."

Describing the high school's fall 1932 football season, the Alameda High Yearbook nicknamed Pete "the Midnight Express," calling him "the spark plug" of Alameda's offense in the game against Piedmont High.

The Alameda High Yearbook also said that Pete was one of the "outstanding performers" in the school's spring 1932 baseball game against Richmond High, saying that "Pete did the heavy hitting."

The Yearbook went on to say that "several scouts from Pacific Coast [minor league] teams have been looking over some of the boys [of Alameda's baseball team] and some of them may win a berth in professional baseball."

Not Pete, though. In 1932, African-American players were banned from professional baseball. Jackie Robinson's breaking of baseball's color line was still 15 years away.

College, however, was still an option.

After graduating from Alameda High Pete enrolled at Marin Junior College, and the Oakland Tribune soon reported on just how successfully he made the transition from high school sports to college. In an article entitled "Pete Big Star," the Tribune wrote: "Coach Scoop Carlson of Marin will shoot Herman Pete, his Negro ace, against Santa Rosa, as he has done so effectively against all teams this year. Pete was the outstanding man on the field in the San Jose (Junior College) contest, spinning off runs of 50 and 60 yards, and putting Marin in position for her two scores, and also shooting the pass to Flynn which was lateraled to Hughes for the second Marin marker." (Oakland Tribune, October 25, 1934)

That same year, the yearbook for San Francisco State Teachers College (later to become San Francisco State University) described the school's football team's preparation for a game against Marin: "Advance publicity on Marin is [scary]...watch Herman Pete and (running back) Charles Meamber do the 100 in 10:2, they told us. 10:2 in the hundred yard dash in 1935 was a fantastic time; Jesse Owens tied a world record that same year running only a second faster. The SF State didn't go as well as expected for Marin, with the State Yearbook later joking that "Herman Pete did run 100 in 10.2 [in the game], but it was going backwards trying to escape the [S.F. State linesmen]."

A year later, an article in the Santa Rosa Press Democrat described how Pete went to work in a football game between Marin and Santa Rosa J.C.

A year later, an article in the Santa Rosa Press Democrat described how Pete went to work in a football game between Marin and Santa Rosa J.C.

When Marin got the ball after a Santa Rosa score, the article went, "then that dark load of dynamite, Herman Pete, really showed his heels. He started off tackle, bounced off two Cub tacklers, into a couple more, went through them, slipped through the entire secondary into the open to score standing up on the greatest run of the game." ("Aerial Attack Gives Winners 2 Touchdowns" Santa Rosa Press Democrat, October 26, 1935)

A few months before the Marin/Santa Rosa football game, Pete showed that the lighting of his "dark load of dynamite" was not confined to the games themselves.

The San Anselmo Herald of April, 1935 reported that during a baseball game between Marin and Santa Rosa Junior College, "Herman Pete, Marin's stellar colored athlete, was at the plate, and (the Santa Rosa coach Sam) Agnew made a remark relating to Pete's color in language not exactly becoming a coach of a college team." ("Marin Jaysee Starts In To Play Baseball" San Anselmo Herald April 25, 1935)

In its own article on the game, the Petaluma Argus-Courier added some details to the incident.

"It all came about when Coach Sam Agnew of the (Santa Rosa) Bear Cub baseball nine insulted First Baseman Herman Pete of the Mariners by using a naughty 'so-and-so' remark while he was instructing Lefty Caldwell, (Santa Rosa) pitcher, to keep the ball away from Pete, who was at bat, because 'that so-and-so might hit it a mile.'" ("Agnew 'Insult' To Be Ignored Petaluma Argus-Courier April 19, 1935)

One can read between the lines that what set Pete and his own coach and fellow players off was that the coach added "black" before the "so-and-so," and that the "so-and-so" probably was a polite substitute in the newspaper for "son-of-a-bitch."

The Herald article went on to say that "Pete, of course, resented the remark, quietly walked over to Agnew, and asked him to apologize.

"Instead of doing so, Agnew added a few words which were overheard by (Marin coach) 'Scoop' Carlson, who resented the disparaging remarks directed to Pete. The game was temporarily held up while several of the players of both teams crowded around the plate, telling Agnew what they thought of his uncalled for poor sportsmanship."

The Woodland Daily Democrat added more details in their report of the incident on the field and its aftermath.

"A 'race insult' assertedly directed at the Negro first baseman of the Marin Junior College varsity yesterday had caused severance of athletic relations between that institution and Santa Rosa Junior College.

"Early in the game, as Herman Pete, the 19-year old Negro, popular and all-around athlete, stepped up to bat, Sam Agnew, former catcher for the San Francisco Seals and now baseball coach at Santa Rosa, yelled out to the pitcher (words of disparagement of the Negro race).

"Pete walked over to Agnew and demanded an apology. Agnew refused to apologize, and a near riot was precipitated. After a half-hour of argument between the teams, the game was renewed...

"A.C. Olney, principal of the Marin school, announced that there would be no resumption of athletic relations until Santa Rosa Junior College authorities forwarded an apology.

"Agnew persisted in his refusal to apologize.

"'I wasn't addressing my remarks to Pete and I told him so,' he said. 'If athletic relations are severed, they can stay so—if it depends upon an apology from me." ("Schools Split—Marin, Santa Rosa In Row Over 'Race Insult'" Woodland Daily Democrat April 19, 1935)

"As Marin left Santa Rosa" after the baseball game, the San Anselmo Herald article explained, "there was talk of severing all athletic relations between the two schools. However...Marin said the breach could be healed by a personal apology by Agnew to Herman Pete. ... The only other way Marin could see their way clear to continue (sports) relations was that Agnew be dismissed."

So what was the result?

"Reports from Santa Rosa Junior College revealed," the Argus-Courier article wrote, "that (Santa Rosa J.C.) President Floyd P. Bailey has sent a letter to A.C. Olney, principal of Marin (Junior College) in which he extended personal apologies and—at the same time—Coach Agnew flatly refused to make apologies."

When Agnew refused to apologize to Pete, the Herald reported, he was "immediately" dismissed from his position as Santa Rosa coach, the newspaper adding that "now all is calm again."

While Pete's reaction to the Santa Rosa coach's words—simply walking up to him and asking for an apology—seem mild by the standards of today's Black athletes, it must be remembered that this was 1935. It was 12 years later that Brooklyn Dodgers owner Branch Rickey told the newly-signed Jackie Robinson that in order for Robinson to survive as the first Black player in major league baseball, he would have to turn his head, "bite his tongue," to use the Southern phrase, and ignore the many times he was called "nigger" by players, coaches, and people in the stands. Otherwise, he'd be out of professional baseball in a hot minute.

Instead, 19 year old Herman Pete held his ground, and it was the offending coach who got himself fired.