Posted April 26, 2021 from Berkeleyside —

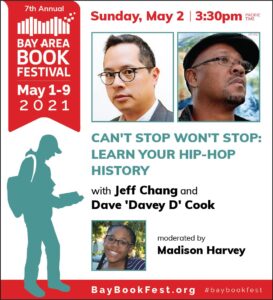

Davey D will appear live May 2 in a free Bay Area Book Festival conversation with Jeff Chang about their co-authored YA version of Chang’s hip-hop classic, ‘Can’t Stop Won’t Stop.’ —

They call Oakland’s own Davey D “the hardest working man in hip-hop” for a reason. Equal parts witness, pioneer and keeper of the genre’s greatest stories, this Bronx-born UC Berkeley grad is a hip-hop Renaissance Man.

Davey D started off as an emcee in New York, then moved to the Bay to learn the secrets of funk and freedom. Here, he was instrumental in founding two major hip-hop institutions: the Bay Area Hip-Hop Coalition, one of the nation’s first hip-hop radio deejay collectives; and the award-winning syndicated show Hard Knock Radio, which reaches close to a million listeners daily.

Davey D started off as an emcee in New York, then moved to the Bay to learn the secrets of funk and freedom. Here, he was instrumental in founding two major hip-hop institutions: the Bay Area Hip-Hop Coalition, one of the nation’s first hip-hop radio deejay collectives; and the award-winning syndicated show Hard Knock Radio, which reaches close to a million listeners daily.

And, because hip-hop is nothing if not an ongoing teachable moment, Davey D also teaches a hugely popular course at San Francisco State University in Hip-Hop, Globalization and the Politics of Identity.

At the upcoming Bay Area Book Festival, he’ll be talking with the other “hip-hop studies star,” Jeff Chang, author of the seminal history of hip-hop, Can’t Stop Won’t Stop. Davey D co-authored the book’s brand-new YA edition with Chang.

Davey D and Jeff will appear live, so you (or your kids) can ask questions. We decided to start things off in advance of the event with a few questions of our own for Davey D:

Can you tell us how your collaboration with Jeff Chang for the young-adult edition of Can’t Stop Won’t Stop came about? We know you lost a manuscript when your computer was stolen. How did that mishap pave the way?

On the 15th anniversary of Can’t Stop Won’t Stop’s publication, Jeff’s editor, Monique, suggested redoing the book for a young adult audience. Jeff had come out with the original book, which was a game-changer, around the same time I lost the manuscript I’d been working on for years. For Can’t Stop Won’t Stop’s YA edition, he tapped me and asked me to work with him. The book I’d lost contained a lot of material about coming up in the Bronx, how I was introduced to the scene as a kid and teenager. The general notes I’d made were still there, so we were able to integrate a lot of those into the young adult edition of the book. I came up in the later part of the 70s; I wasn’t there for hip-hop’s earliest days, but I was there. It was great to look at my old journals and remember what it was like to have a birds’ eye view (seeing Grandmaster Flash perform, for example) into a certain time period. We both wanted to give those jewels to young people, and let them know that the baton is being passed to them.

On the 15th anniversary of Can’t Stop Won’t Stop’s publication, Jeff’s editor, Monique, suggested redoing the book for a young adult audience. Jeff had come out with the original book, which was a game-changer, around the same time I lost the manuscript I’d been working on for years. For Can’t Stop Won’t Stop’s YA edition, he tapped me and asked me to work with him. The book I’d lost contained a lot of material about coming up in the Bronx, how I was introduced to the scene as a kid and teenager. The general notes I’d made were still there, so we were able to integrate a lot of those into the young adult edition of the book. I came up in the later part of the 70s; I wasn’t there for hip-hop’s earliest days, but I was there. It was great to look at my old journals and remember what it was like to have a birds’ eye view (seeing Grandmaster Flash perform, for example) into a certain time period. We both wanted to give those jewels to young people, and let them know that the baton is being passed to them.

What does it mean to adapt this specific book for younger audiences? What was that process like?

We didn’t want to dumb it down, and the YA audience doesn’t want it dumbed down either. Young adults don’t want to be at the kiddie table! What makes it a young adult book is how we referenced it. If you have someone who grew up in the 90s, we might make a reference to Public Enemy or drop names like Ice Cube with NWA. [With the YA focus] we keep those important stories, but are more intentional about making comparisons: we say “Ice Cube grew up in Compton, like Kendrick Lamar.” Or, “Ice Cube’s like J. Cole.”

Does that approach also come into play with the social-justice aspects of hip-hop that the book emphasizes?

Absolutely. We were vigorous in terms of presenting the material through a social justice cultural lens. We have a generation that wasn’t even born at the time of the Rodney King verdict in LA in 1992, but they do know Ferguson, Freddy Gray in Baltimore, Oscar Grant in Oakland. When we tell the story of hip-hop, which I think is universal in terms of the political and social conditions faced by marginalized communities, that’s the story that’s important to be told, and it’s a continuous story that many communities have faced. Policies that target these communities today were also were in place in 1968, in the seventies, in the nineties, and they’re still in place in the 2000s. Instead of reinventing the wheel, we can build off that and see what worked and didn’t. What approaches were deployed then that we can learn from now?

Absolutely. We were vigorous in terms of presenting the material through a social justice cultural lens. We have a generation that wasn’t even born at the time of the Rodney King verdict in LA in 1992, but they do know Ferguson, Freddy Gray in Baltimore, Oscar Grant in Oakland. When we tell the story of hip-hop, which I think is universal in terms of the political and social conditions faced by marginalized communities, that’s the story that’s important to be told, and it’s a continuous story that many communities have faced. Policies that target these communities today were also were in place in 1968, in the seventies, in the nineties, and they’re still in place in the 2000s. Instead of reinventing the wheel, we can build off that and see what worked and didn’t. What approaches were deployed then that we can learn from now?

For example, we talk about various moments in hip-hop when young people at the time did amazing things (and even if we’re writing about Chuck D and Grandmaster Flash, who are in their 60s now, the stories we’re telling about them happened when they were 17 and 18 and 20). We’re giving young people a blueprint so they can see themselves. We talk about the young adults who were Crips and Bloods in LA and in New York in the Latin Quarter, who met up in the 80s and said “let’s make peace, let’s deal with the crack epidemic in our communities, let’s stop violence.” Young people today now can see how those figures from the past solved it, and say “these are the same types of people who were being targeted in Ferguson.”

How does writing style come into play when you’re trying to reach young adults?

We’re not giving tons of theories; we’re telling stories. When you look at communities all around the world, we tell stories, fables, allegories…those are what stick with people and make it relatable. When we give you the gang narratives, we give you the stories behind them. We look at everything through a lens of storytelling. We’re not being the definitive historians; we’re recognizing that there are tons of people that have deeper stories from behind the ropes. For instance, the YA audience can pick up my story and be curious enough to use my story as a conduit to other stories. What we’re doing is giving YA kids the first course of a ten-course meal, to intrigue them enough to seek out other storytellers.

We’re not giving tons of theories; we’re telling stories. When you look at communities all around the world, we tell stories, fables, allegories…those are what stick with people and make it relatable. When we give you the gang narratives, we give you the stories behind them. We look at everything through a lens of storytelling. We’re not being the definitive historians; we’re recognizing that there are tons of people that have deeper stories from behind the ropes. For instance, the YA audience can pick up my story and be curious enough to use my story as a conduit to other stories. What we’re doing is giving YA kids the first course of a ten-course meal, to intrigue them enough to seek out other storytellers.

The stories sound like they’re as layered and interconnected as the samplings and influences in the songs themselves.

Absolutely, and that’s intentional. It’s very aligned with what hip-hop is all about. It’s like when you’re listening to Public Enemy and thinking “what’s that sample/riff in this song? Oh, it’s James Brown. Let’s track down that James Brown song.” Or, “what’s that sax solo? It’s Chick Correa or Wes Montgomery or Coltrane.” You get curious, and you look at the back of the album and you find the provenance.

You’ve been there for a lot of amazing hip-hop milestones. Can you talk about what it was like to be present for the historic 1997 Hip-Hop Peace Summit in Chicago?

Two weeks after Tupac [Shakur] was killed, Louis Farrakhan put on a call for [leading figures in hip-hop and rap] to come to Chicago. And when the call came, everybody dropped what they were doing and went. Ice Cube shut down filming of his movie the morning he heard, and chartered a plane and flew out immediately. Another rapper, Fat Joe, was in a bowling alley when he heard. He was furious that Ice Cube and Westside Connection had done disparaging songs about him and betrayed his friendship and added fuel to the fire. So when he was in that bowling alley, Fat Joe heard about the summit, but he was scared of flying and he hated driving. But he asked, “is Ice Cube gonna be there?” and when the answer was yes, he got in his car and started driving. He showed up, in the middle of a Chicago snowstorm, with his bowling shoes on!

What was the most unforgettable moment you witnessed at the summit?

We were all asked not to speak about everything that was said at the summit. A lot of people were very earnest, honest, vulnerable and let their guard down, revealed a lot of personal background information: that was necessary, in order for peace to be established. But I can tell you that many of us got to meet Kwame Ture (SNCC), who facilitated the meeting. And everyone was there, from Too Short to Snoop Dogg. The mentality was “let’s solve this; we’re not leaving this room til it’s resolved.” I was the only journalist that was there and was entrusted with that information and that commitment to be a part of that process, and to respect what people talked about that day.

We were all asked not to speak about everything that was said at the summit. A lot of people were very earnest, honest, vulnerable and let their guard down, revealed a lot of personal background information: that was necessary, in order for peace to be established. But I can tell you that many of us got to meet Kwame Ture (SNCC), who facilitated the meeting. And everyone was there, from Too Short to Snoop Dogg. The mentality was “let’s solve this; we’re not leaving this room til it’s resolved.” I was the only journalist that was there and was entrusted with that information and that commitment to be a part of that process, and to respect what people talked about that day.

It was a beautiful and moving experience I’ll never forget. One amazing moment was seeing Ice Cube and Common coming into the room, and Ice Cube saying “I have beef with this man, and I want to say I’m sorry.” Everyone who was there spoke from the heart. And there was a long footprint to that summit. After that, Snoop Dogg started to teach and do his football league for kids, and things shifted.

Later, we saw other beefs emerge, but that’s a younger generation who wasn’t in that room. Peace is ongoing: it doesn’t just happen and stay.

Last year, you told The Ringer, “If you said New York was a lion, L.A. was a lion, the Bay would be a tiger.” Can you elaborate on what makes the Bay Area hip-hop scene special?

When you’re from NYC, you go anywhere around the country, and people say “let me soak up what you gotta say, because NYC is the mecca.” Same with LA. The financial capital and the entertainment capital. But certain cities have a real independent streak. When I moved out here, there was no “ooooh, you’re from New York.” No one was in awe.

I found that the Bay had a scene they were very proud of and was very entrenched in the Black community: a dance and funk scene going back to the sixties. This independent scene based around funk informs many of the people who, when they see hip-hop, their initial reaction isn’t to be awestruck. It’s not “I’m gonna replicate this wholesale.” It’s more like “we’re gonna do this independently and do this via hyperlocal marketing…I’m gonna sell all my records in Oakland. I don’t have to be on ‘Soul Train’ or MTV. I can go sell tapes in Santa Rosa, San Jose, Vallejo, East Palo Alto, for five or ten dollars, and keep most of my money.”

I found that the Bay had a scene they were very proud of and was very entrenched in the Black community: a dance and funk scene going back to the sixties. This independent scene based around funk informs many of the people who, when they see hip-hop, their initial reaction isn’t to be awestruck. It’s not “I’m gonna replicate this wholesale.” It’s more like “we’re gonna do this independently and do this via hyperlocal marketing…I’m gonna sell all my records in Oakland. I don’t have to be on ‘Soul Train’ or MTV. I can go sell tapes in Santa Rosa, San Jose, Vallejo, East Palo Alto, for five or ten dollars, and keep most of my money.”

The Bay is a powerhouse that established an independent game that many around the country emulated; it’s a creative center that’s hella cool and it’s not necessarily trying to get the attention. It’s where a lot of groups have broken because of independent radio, and that became a prototype for crossover stations across the country. These tracks weren’t getting played by highfalutin’ people in a highrise. The people playing these tracks were in their 20s, deejays whose creativity was respected, and they were able to implement that creativity…to the point where big powerhouse stations in LA were contacting our independent radio people to find out what they’re playing and what music they’re breaking.

What about the current Bay Area hip-hop scene excites you the most?

So many things. Oakland’s RyanNicole stands out…they’re an incredible artist, emcee and singer, also a filmmaker. I’m excited about [“Fruitvale Station” and “Black Panther” filmmaker] Ryan Coogler, who’s very hip-hop oriented. I’m excited about the Mt. Westmore project with Too Short, Snoop, B40, and Ice Cube coming together to form a supergroup.

Artists like Sol Development bring a revolutionary social-justice spirit to the table. So does muralist Rachel Wolfe-Goldsmith (aka Wolfpack). It’s all part of the expression and the Renaissance. When I look at hip-hop now, it’s not just the music tip, it’s how you’ve grown. I’m seeing people who are getting bills passed and holding office and they don’t have records, but what they do is hip-hop. They come out of that community.