Posted March 16, 2021 from KQED Arts —

The sun shined down on West Oakland last Wednesday as I was greeted with a warm, welcoming, COVID-cautious elbow bump from Ericka Huggins.

Huggins, the former director of the Black Panther Party’s Oakland Community School, stood masked among a scattered crowd of people on the 1.3-mile stretch of greenway that bisects Mandela Parkway in West Oakland. It’s here that the Cypress Structure collapsed in the '89 quake—and also where two months prior in that same year, Black Panther Party cofounder Dr. Huey P. Newton was shot and killed just a few blocks away.

And yet—as I overheard one person say during Wednesday’s gathering—“this isn’t where he died, this is where he lived.”

Last Wednesday, Feb. 17, would’ve been Dr. Newton’s 79th birthday. To help celebrate were newly minted street signs on a three-block section of 9th Street, now officially rechristened Dr. Huey P. Newton Way.

A two-story home on Center street and 9th Street in West Oakland is now home to a mural dedicated to the women of the Black Panther Party. Artwork by Rachel Wolfe-Goldsmith.

After Fredrika Newton, Dr. Newton’s widow and president of the Dr. Huey P. Newton Foundation, ceremoniously removed the cloth that covered the new street sign on 9th Street and Mandela Parkway, the crowd made its way to the intersection of 9th and Center Streets. That’s where a freshly painted mural dedicated to the women of the Black Panther Party now radiates from the broad side of a two-story Victorian home.

Lead artist Rachel Wolfe-Goldsmith worked with other artists and community members on the #SayHerName: Women of the Black Panther Party Mural Project, an initiative spearheaded by homeowner JiLchristina Vest that honors the names of the largely overlooked women of the Black Panther Party. Towering images of women supplying groceries and carrying guns, drawn from photos taken by Stephen Shames, are accompanied by the written names of over 250 women—all former Panthers.

There aren't that many public displays honoring the Black Panthers in Oakland. The new mural and street signs join a meager collection: a small sign on the corner of 55th and Market Streets, a mural on 14th and Peralta Streets, the Huey P. Newton Lounge at Merritt College and Lil Bobby Hutton Grove in DeFremery Park.

But countless Panther flags, shirts, and tattoos on the skin of the people in this community all stand as evidence of a widely-known fact: this is Panther territory.

Even beyond Oakland's city limits, the Black Panther Party is once again in the larger public consciousness.

Shaka King’s recently released film Judas and the Black Messiah has reinvigorated people’s interest in the life, politics, and assassination of the Illinois Black Panther Party chapter's chairman, Fred Hampton. (The film is told from the perspective of William O'Neal, the informant who assisted the FBI in bringing Hampton down.)

But well before Judas and the Black Messiah, and the murals and new signage in Oakland, the legacy of the Party and the individuals involved has long been a personal interest of mine.

I once held back childlike excitement when Ericka Huggins and archivist Lisbet Tellefsen allowed me to look through the old photos of the Black Panther's Oakland Community School. And I defeated pterodactyl-sized stomach butterflies of nervousness before asking Fredrika Newton intimate questions about her relationship with Dr. Newton.

I’ve talked to educational counselor and former Panther Massai Minters at UCLA's Campbell Hall where Bunchy Carter and John Huggins were assassinated, attended an event at Merritt College where famed Black Panther Party illustrator Emory Douglas spoke about his book Black Panther: The Revolutionary Art of Emory Douglas, and even sat in a small apartment with a sick Ronald "Elder" Freeman, discussing how to address the ills of society while simultaneously looking for his medicine. Elder has since passed, but his words linger.

Through these interactions, as well as reading books and watching documentaries, I’ve gained a certain understanding about the Panthers: terrorized by the government, stigmatized by the media, and loved by the people (well, some of the people). The Panthers fought to save their community from the failures of a capitalist system, while simultaneously dealing with their own personal issues—issues that were largely the byproducts of a capitalist system.

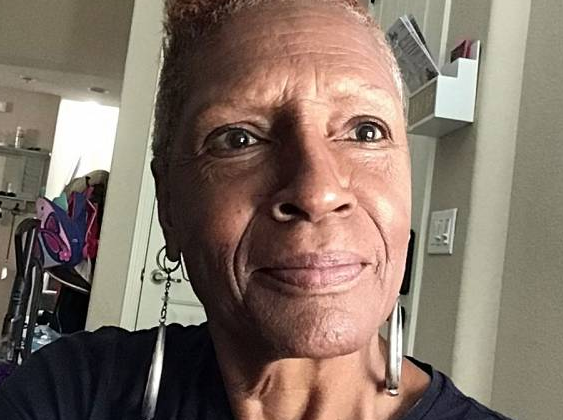

Before becoming a reverend, Cheryl Dawson was a member of the Black Panther Party. Now, she's part of a towering mural in West Oakland paying tribute to the women of the Black Panther Party.

Beyond the legacy of the Black Panther Party as a whole, I often think about the stories of the individual people involved. People whose stories haven't been fully told. People like the Rev. Cheryl Dawson.

"I took the political structure that I learned in the Party, and combined it with the information that I had about womanist theory and I took that work to the Congo—the Democratic Republic of the Congo—did I tell you about that?” Dawson asks me over the phone.

I tell her that during our two previous conversations she hadn’t mentioned that, so I’m glad she called back.

She tells me that about a decade ago she led empowerment workshops with women in Uganda and Haiti as well, using principles she developed when she was selling copies of the Black Panther Party newspaper on the corner of Alcatraz Avenue and Adeline Street in Berkeley back in the day.

In an earlier conversation, she mentions another chapter in her life that was also heavily influenced by her time with the Party.

Starting in the early '80s Dawson worked in and out of prisons, developing programs for women who are incarcerated. She spent the final decade of her career working as the Rehabilitation Services Coordinator in the San Francisco County Sheriff Office’s Women’s Resource Center. That’s where she implemented a curriculum to empower women through lectures, through the use of popular media to inspire critical thinking, and by asking class attendees to reflect on "their own cultural experiences and injustices”. Upon leaving her position last year, the San Francisco Sheriff's Department honored her commitment to the work by naming Dec. 20 "Rev. Cheryl Dawson Day."

I couldn't help but wonder: How do you pivot from working for a revolutionary liberation organization to working for the very institution that incarcerates people?

“I was working in the same sacred spaces,” explains Dawson. “The same tight corners, the same buried holes in the ground that I had tested, and walked in, and helped raise people up from when I was working in the Party ... The pain that women wore in the prison is the same pain that I saw in the community from which they had come.”

Simply put, Dawson saw the position as an opportunity to get deeper into the system and make a change from within.

As a consultant at the federal prison in Dublin, she recalls sitting outside of solitary confinement, kneeling down on the cement floor, and talking through the slit in the steel door where the food was passed through. “I was trying to get a glimpse of the woman I was talking to,” says Dawson. “To just hold her gaze for a moment and try to give her hope for tomorrow.”

She did this work while continuing to face "that same deep intimate pain” that she experienced as a young girl; the pain that pushed her to join the Party in the first place.

As a child, Dawson lived in Codornices Village, a housing project on land leased from UC Berkeley to house wartime workers and their families in the 40s, many of them African American. It’s no coincidence that in the 1960s, when the housing projects were closed and the property was returned to UC Berkeley, the "Negro" population of Albany went from 1,778 people in 1950 down to just 75 people in 1960.

Afterward, Dawson spent some time in Oakland, but Berkeley was her home. She lived one block to the white side of the city’s racial housing dividing line, formerly known as Grove street (now Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard).

At Berkeley's Longfellow Elementary School, despite being in the Black neighborhood of South Berkeley, she saw racism firsthand. In class, Dawson says, she and the other Black kids were routinely overlooked when they raised their hands and over-punished when they got in trouble.

She says a brother as dark as she was once got in trouble, and a white teacher grabbed him by the scruff of his neck and put him under one of those old-fashioned wooden desks. The teacher then sat down and scooted her chair in. “She pinned him in like he was a dog or cat or something,” says Dawson. "The only thing he could do is look out from under the desk."

The memory of the disobedient boy and the heavy-handed punishment stuck with her. Shortly afterward she learned about social workers, and how they helped people; especially people who looked like her. “At a very young age," says Dawson, "I had a desire to do that, it was stamped in my heart. Unbeknownst to me, it would continue to manifest for the remainder of my life.”

She went on to attend Willard Junior High, which was much whiter, and well above the racial dividing line. After attending Berkeley High for the majority of her high school years, she graduated from Oakland Tech and went on to Cal State East Bay.

While she was in college, Dawson was invited to an event at Oakland City College where Black Panther Party for Self-Defense co-founder Bobby Seale was speaking. And the rest was history.

Rev. Dawson has no issue discussing details of her time in the Party, like bundling up her infant daughter at the early hour of "can’t see in the morning" so they could get to the Panther headquarters, serve the people and take political classes, only to return home at "can't see at night."

But what stands out from our conversation is Dawson periodically pausing to ask her grandchildren to "be careful while you're doing that."

Community service starts at home.

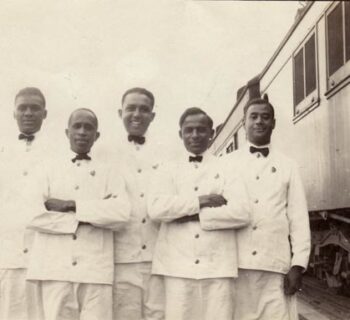

Dawson tells me she's inspired by her great uncle, who left the south on a flatbed truck after being chased by the Klan. Once he settled in California, he sent for his sister, Dawson's grandmother. Not too long after arriving in the Bay Area, Dawson's grandmother and grandfather were wed through a marriage broker in West Oakland.

Speaking highly of her four children, Dawson proudly mentions that two of her sons chose to change their names upon adulthood in an effort to shed their slave names.

Dawson holds a master's degree in womanist theology from the American Baptist Seminary at UC Berkeley's Graduate Theological Union, as well as an M.A. in women’s spirituality from San Francisco's California Institute of Integral Studies. She was ordained as a reverend about five years ago, at the same place she served: the historic Beth Eden Baptist Church in West Oakland.

She tells me she just recently returned to the church, as nowadays spends most of her time with the grandchildren I heard in the background on our calls. And of course, she plans to take them to see the new mural featuring images of her comrades in West Oakland.

"The mural brings us from the margins to the center," says Dawson of the artwork's significance. “To turn the light on and say: I see you. And to further extend my view of connectivity and say, 'I see you, because you are me.' Just that alone is life-saving. And that’s what we were about in the Party: saving the lives of our people.”