NBA.com

“Have you ever met anyone who said they didn’t like Phil Chenier?” - Steve Buckhantz.

No.

Over the last five decades, Phil Chenier has graced Washington D.C. with his basketball prowess, first as a player and then as a broadcaster. Very few have earned the amount of respect over that time as Chenier, who may be one of the coolest cats to have ever done it.

On March 23rd, Chenier will watch his #45 be lifted to the rafters of Capital One Arena, as his jersey will hang with the greatest to ever put on a Bullets/Wizards uniform.

A 3-time NBA All-Star, who poured in nearly 10,000 points in his 11-year career, Chenier will join Wes Unseld (#41), Elvin Hayes (#11), Gus Johnson (#25), and Earl Monroe (#10) as the fifth number retired by the organization.

Chenier spent nine seasons with the Bullets and then spent another 33 as the team’s primary television color analyst, becoming one of the most synonymous names with Washington D.C. basketball.

He’s seen a lot of hoops, from a lot of different angles, but if it weren’t for a teacher of his back in junior high school, things may have turned out differently.

Early Life

Chenier grew up in Berkeley, California and believe it or not, his first love wasn’t basketball. He was initially introduced to baseball and began playing little league at nine years old. He remembered becoming a San Francisco Giants fan when they moved to the Bay Area in 1958 and then played baseball through junior high, where he developed into one of the better pitchers in the region.

He played basketball around the park, but it wasn’t something he took too seriously, especially because he was a great baseball player.

That changed the summer after his eighth-grade season, where he played for Willard Junior High School in Berkeley. Once the season was over, he went into the gym by himself to shoot, and was met by one of the school’s first-year teachers, a man named Don Doorlag.

“He [Doorlag] starts talking to me and he says ‘do you like to play basketball?’" Chenier recalled. "I said yeah, he said, ‘Do you want to get good, you have to do this and that, here let me show you.’ He was about 6’6”, played college ball at some place in Michigan, and this was his first year at Willard Junior High. He starts working with me, and he tells me to come on back and I’ll work with you some more. So, every day after school I would start working with him and that was the beginning of my love for basketball.”

He said it was Doorlag who lit a fire in him and gave him tips and little pointers that he would keep with him all the way through his NBA career.

The next year, Chenier’s ninth-grade season and final one at Willard, he wanted to show Doorlag what he worked on over the summer, but the teacher was gone. He didn’t work at the school anymore, but Chenier still went on to lead his ninth-grade team in scoring and he felt a lot of gratification from all the hard work he put in the year before and the previous summer.

Chenier was never able to locate Doorlag until about 50 years later, when the Bullets former chaplain, Joel Freeman, was writing a book and wanted Chenier’s story about his old junior high school teacher. Once Chenier told him about Doorlag, Freeman said he was going to find him. And he did. He tracked him down outside of Oregon, and the next time the Wizards went to play the Trail Blazers in Portland, Chenier, and the one he credited for starting his love for basketball, reconnected. It was a reunion Chenier still cherishes today and something he’ll never forget.

After his junior high career was done, it was time to move on to Berkeley High School, where Chenier first thought he would be playing his 10th grade season on the JV team.

“I’m playing on summer league teams, playing at the park, and I’m ready to drop baseball, but my dad wouldn’t let me do that, so we come out in the 10th grade and I’m thinking about trying out for JV and on the first day the varsity coach comes in and says ‘I want you to come into the varsity room.’ I end up playing varsity, was a starter and the team’s second leading scorer, and at that point I went to another level. Everything I did was eat, sleep, and dream basketball.”

He would play two to three times a day and by the time his senior year rolled around, he was an All-American shooting guard and was being recruited by some of the top schools in the country.

He was heavily recruited by John Wooden and UCLA, a powerhouse at that time in the late 1960’s. But despite taking a few trips down to Westwood, Chenier wanted to be a Cal Golden Bear. He grew up watching the Golden Bears in the late 1950’s and became a fan. He watched coach Pete Newell lead them to a National Championship in 1959, a team that had Darrall Imhoff, who would be a first-round NBA draft pick in 1960. That was Chenier’s image of college basketball and was something that stuck with him when it was his turn to head to college. He knew UCLA already had tradition and a great reputation, but he wanted to stay local and build something great for UC Berkeley. He also knew Berkeley had a great recruiting class the year before his, which included Charles Johnson, who ironically enough would be the player the Bullets would acquire because of Chenier’s injury in 1978 that helped them win the 1978 NBA Championship.

Chenier played the 1969 season on Cal’s freshmen team, before playing his next two seasons for the varsity squad, where in his junior year he averaged nearly 17 points per game and would be named first-team All-Pac 8.

Following his junior season at Cal, Chenier was invited to the Pan American USA Basketball trial camp in Colorado Springs, which was the first time he was able to compete with the best players in the country.

“It was that summer I was invited to go to Pan Am trial camp in Colorado Springs, and we had guys from all over the country there. AAU wasn’t nearly as big then, so you played local summer league, but you weren’t exposed to playing guys from all over. But, this camp was that, so you had guys from New York, guys from the south, guys from all over and it was really good experience. I didn’t make the team, but I played well and that’s where Bob Ferry from the Bullets saw me, and at that point I was being talked about as being one of the top players in my class and one to look at for the draft,” said Chenier.

The 1971 NBA Draft had already passed, but later that summer, the NBA was set to have its first ever supplemental hardship draft, which would allow underclassmen to be drafted into the NBA. Prior to 1971, players had to complete four years of college before entering the league, or if they left early they could not enter until their class graduated. After Spencer Haywood won his Supreme Court case against the NBA, it opened the door for underclassmen and high school players to be eligible for the league. In September of 1971, the NBA held its supplemental hardship draft, and the Bullets would select Chenier with the fourth pick. By picking Chenier, the team forfeited their first-round pick in 1972.

Pro Career

The hardship draft was so close to the start of the 1971-72 season, Chenier didn’t get to Baltimore until the end of training camp.

“I remember coming to a team that just lost in the Finals,” Phil explained when discussing his rookie year in the NBA. "I remember watching the team play in New York in Game 7 and I watched Earl [Monroe], and Gus [Johnson] and Freddy Carter, not knowing that in three or four months that I’d be playing with them. Earl looked after me, Gus stepped in and helped me find a place, helped me find a car and find contacts around city. On the road he would look out for me and take me to dinner, so I had a very protected first year experience."

The seamless transition paid off on the court too, as Chenier averaged 12.3 points per game his rookie season and helped the Bullets reach the playoffs, where they lost in the first round to the Knicks.

Chenier described his first season as a flash, but did remember scoring 28 points against the Lakers on national television. A game broadcasted by the great Bill Russell, who also hailed from Oakland and took a liking to the rookie, labeling him the ‘hardship kid.’ Phil credited much of his early success to his first NBA coach, Gene Shue, who had a great understanding of his game and taught him the importance of using his hands on defense. Shue explained to Chenier how teams would try and hand check him to slow him down and different elements he’d need to use to counter that.

Before Chenier’s second season, he recalled spending most of that summer going to the Jewish Community Center (JCC) in Baltimore to work with what would now be considered a strength and conditioning coach. It was more unusual at the time, but Chenier would go in three times per week, sometimes accompanied by a teammate, but sometimes by himself, to try and get stronger for the next year. He explained how back then guys would lift in the offseason, but once the season started it would be rare to continue to take part in weight training, so he wanted to enter the year in the best shape possible.

When he arrived for his second season, the team had dealt his good friend Gus Johnson to Phoenix, which was his awakening that this was a business. The Bullets had also acquired Elvin Hayes from Houston and drafted Kevin Porter, who Chenier said he instantly clicked with.

It was in his second season when Chenier had his best shooting game of his career. On December 6th, 1972, he made 22 shots and finished with 53 points. A total that remains the highest point total in a non-overtime game in franchise history. Bradley Beal approached this number earlier this season, also against the Blazers, but finished with 51 points.

Chenier said he still remembered that night and joked that while years later everyone told him they were at the game, he would laugh, because the attendance that night at the Civic Center was just 1,888, and he’d tell them, “I would have seen you if you were there.”

“After the game, I remember it was me, Kevin Porter and Tom Patterson, we got in the car, and we didn’t have cell phones then, so I had to call back home the next morning to tell my mom and my family what I had done. But that night, we rode up and down 40 West, just looking for some food, eventually finding this fast food joint, got a burger and milkshake, and laughed about the night. I remember Porter said ‘man I can’t believe you shot like that.’ It was a great experience.”

The Bullets once again came up short that year against the Knicks in the first round of the playoffs, something that became a trend for Chenier and the Bullets in the early parts of his career.

The 1973-74 season saw the Bullets move from Baltimore to Washington, where they were known as the Capital Bullets for one year. Chenier would average 21.9 points per game in his third season and was named to his first NBA All-Star Game. He was now the team’s leading scorer and along with Elvin Hayes had formed a great one – two tandem in the league, with the two scorers averaging over 21 points per game. But, for the third straight year, the Bullets were eliminated in the first round by the Knicks.

By the time the 1974-75 season came, the Bullets, now known as the Washington Bullets, had their mind set on beating the Knicks. But, they wound up playing Buffalo in the first round of the playoffs, and they beat the Braves in seven games. Chenier scored a game-high 39 points on 13/18 shooting in Game 7, out-dueling the great Bob McAdoo, who finished with 36 as the Bullets topped the Braves, 115-96.

They then beat the Celtics in six games, setting up for Chenier’s first trip to an NBA Finals. It seemed to be a storybook tale, as the opponent was the Golden State Warriors, which meant Chenier would get to play in front of his family and friends back in the Bay Area as the Bullets looked to win their first ever championship.

But, fate wasn’t too kind for Chenier as the Warriors upset the Bullets, 4-0, the second time Washington had been swept in the Finals that decade. While the result wasn’t what Chenier hoped for, he still remembered that season as one of the fondest of his career, helping lead his team to the Finals and being able to play in his first NBA Finals in front of his mom, dad, brothers, cousins, aunts and uncles.

Chenier enjoyed a few more complete seasons, scoring around 20 points per game, but then back injuries began to hinder his ability, both physically and mentally.

The 1977-78 season was a difficult one for Chenier, as a back injury ended his season in January, which resulted in the team bringing in his former college teammate, Charles Johnson. Before the season, the team went out and acquired Bobby Dandridge from Milwaukee and Bobby D gave the team another strong perimeter threat, one that could defend some of the great players in the league. While the team had a modest regular season, due to numerous injuries, they caught fire in the postseason, and went on to win the 1978 NBA Championship, beating the Seattle Super Sonics in seven games. Chenier loved his teammates and was happy the team he spent his whole career with finally got over the hump. But, there was also a sense of sadness that he couldn’t be out there with them to celebrate the title.

Injuries continued to hamper the rest of his career in D.C. and he would only play in 47 more games for the Bullets and was then traded to the Pacers during the 1979-80 season. He played in nine games in his final season with the Golden State Warriors, but back problems forced him to retire at age 31. He finished his career with 9,931 points and ranks seventh all-time in Bullets/Wizards history.

Moving on to Broadcasting

After Chenier’s playing career was over, he returned to the D.C. area, and was working for a Boys & Girls Club, when an opportunity arose.

After Chenier’s playing career was over, he returned to the D.C. area, and was working for a Boys & Girls Club, when an opportunity arose.

“I stumbled into it. When I was back in college, my junior year, we went out and played a tournament and one team there was Harvard. They had James Brown and Floyd Lewis, who were from DC. Brown was a 6’6” guard and we went at each other, a real spirited competition. Then we got to talking after the game, and he asked us what we were doing and invited us to come by their hotel after the game, and from there it sparked a friendship,” Chenier told about his initial relationship with Brown, which led to his broadcasting start.

Fast forward about 12 years later to the mid 1980’s and Brown, a D.C. native, was broadcasting college games in the area and then started calling some Bullets games. Brown was working for a few different stations and wound up having some scheduling conflicts, which is when he reached out to Chenier and asked if he would be interested to fill in as a color analyst. Chenier had no broadcast experience and told Brown that, but JB encouraged his friend to just talk about basketball, and Chenier agreed and said he’d give it a shot. He then began filling in for Brown more regularly and would call games with Charlie Neal, while still working at the Boys & Girls Club in D.C. He caught on to broadcasting quickly and called the games similar to how he played, with a smooth flow. The Bullets were then signing on with a cable network, Home Team Sports, and they were looking for a color analyst. Chenier said it was as simple as calling up his old teammate, Wes Unseld, who was in management with the Bullets, and Unseld told him the job was his. Chenier said he didn’t even have to send in an audition tape, but he was now the Bullets full time color analyst.

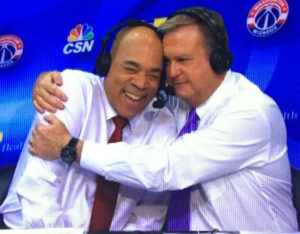

He called games with Mel Proctor for Home Team Sports, until his longest tenured partner, Steve Buckhantz, took over as the play-by-play man for the 1996-1997 season. The pair then called Wizards games together for the next two decades, forming quite a friendship and a close bond.

“When he came on and started traveling full-time, the transition was smooth, he was like a brother from another mother,” Chenier said.

Their chemistry would grow over the years and Phil explained how sometimes they wouldn’t even need to use words to communicate.

“Sometimes Buck and I would just look at each other and we knew what the other was thinking, or we’d spend time talking about the other team’s players before the game, so we knew how each other felt about certain guys without saying it on the air,” Chenier continued.

Buckhantz, a native of Northern Virginia, grew up watching Chenier and the Bullets, and before they became close friends, was a big fan of Phil the basketball player.

“The first time I actually got to do games with Phil, I had to pinch myself, to make sure I realized I was working with a guy who I idolized. And in my 20th year of doing games with Phil, I still had to pinch myself to realize that I was doing games with a guy I once idolized,” said Buckhantz, who continues to call games for the Wizards on NBC Sports Washington.

“People used to say to us, ‘it seems like you guys really like each other’, and we’d say yes we do. We would spend all that time together, six months of every year for 20 years and then a lot of time in the offseason, playing golf, going on vacations, and we did that because we had and still have a close, genuine friendship."

While they formed a great broadcasting pair, their friendship really grew over time, and Chenier said it was the dinners, the traveling, and life on the road that he remembered most. There was the one time when they got kicked out of a cab in Indiana or the one when they were taken to the wrong arena at a preseason game in Ohio. They probably have enough stories to write a book together someday as the two spent about 20 years traveling the country with the Wizards.

After spending the better part of five decades with the organization, Chenier, along with many of his former teammates, friends and his family, will watch as his #45 gets lifted to the rafters with the other greats in Bullets/Wizards history. He said he’s been thinking about the night and doesn’t want to leave anyone out when thanking all the people who have played a major role in his life.

“I don’t know what my emotions will be like, but I told them I ain’t too proud to cry, if that’s what happens, that’s what happens. I just want to share this reunion with everyone who’s had some type of impact, and I’d like for them to be recognized too.”

The players on the current Wizards team who know Phil only address him one way: Legend.

On March 23rd, the one they call Legend, the one who’s had as big of an impact on this franchise as anyone, the one who has exemplified class in every sense of the word, will watch as he’s enshrined into Bullets/Wizards lore.